A Better Future for the Planet Earth

Gretchen C. Daily Interview Summary

Prof. Gretchen C. Daily (USA)

Biologist

born on October 19th, 1964, Washington D.C.

Bing Professor of Environmental Science in the Department of Biology,

Director of the Center for Conservation Biology, and

Senior Fellow at the Stanford Woods Institute, at Stanford University,

Co-Founder and Faculty Director of the Natural Capital Project

Childhood

I was born in Washington D.C. in 1964. Pretty soon after that my dad moved to West Germany with me and my mother. My dad was an eye doctor. And he wanted my family to see more of the world and not be too American or too narrow in our experience and thinking about the world.

Then we came back to the US and we lived in California, in the San Francisco Bay Area. I got to run around outside every day. I loved having pets and wildlife all around. My father helped a lot of people who sometimes couldn’t pay for medical care (there is no universal medical care in the US, unfortunately) and those people would give us pets as a ‘thank you’. So we got a cat, some ducks, and more. My favorite was a wonderful dog - half husky and half wolf — named Mishka, and I ran around with her in the hills chasing rabbits and deer. Thanks to these pets and the time outside with them, I developed a deep fascination for nature and love for being out in it.

In West Germany, 1 year old

Then when I was twelve my father and mother moved to West Germany again. I missed the nature that we had so much of in California. In Germany, it was nice, too, but so much more managed. I gradually got accustomed to the more managed types of nature, especially once I could feel how much people cared about it, and had cared about it for more than a thousand years. The culture in Germany involves deep attachment to forest. People there go walking in the forest every weekend. We had forest nearby and I would go biking over to that forest by myself. I loved that.

Shocked by Acid Rain

So for me this was in the 1970’s and 1980’s when acid rain became a huge issue in Germany. It destroyed a lot of forest. In German, it’s called "Waldsterben," forest death. So I was twelve when this was happening and there were many demonstrations. I nearly cry even now, remembering it — the demonstrations had such a powerful effect on me. Seeing hundreds of thousands or I think even sometimes millions of people marching in the city streets to protest this forest death, and protest how societies were developing, and how we were kind of developing at all cost, any cost to nature — and to our own wellbeing, as we are intimately embedded in the web of life.

As a young girl and teenager, I first of all was amazed that something like acid could come out of the sky. I had never heard of anything like that! Enough to kill the German forest and kill the fish and frogs in the lakes of Scandinavia. I thought back then that people could do something about the acid rain issue. I was really inspired to see so much caring and so much energy going into trying to change the path of society. So I felt that I should do something.

You know, you can feel the connection between nature and people in the culture, in the history, and you can feel it in people’s hearts. But you don’t feel it in the way we develop, in the way we take financial decisions and management decisions, you don’t feel it in most policy or planning. So back then I was very hopeful and I thought, well I’ll become a scientist and if I’m going to understand nature and help change policy, finance, and management, you know, I will contribute the most as a scientist.

To the World of Science

First scientific research at 16

When I was a bit older, about fifteen or sixteen, I took chemistry and I had a teacher named Dan Holmquist — and I always remember him. One morning on the radio I heard that there was a chance to do a research project and enter a competition. So I went to Mr. Holmquist that day and I asked him if I could study acid rain with him, because that was all in the news and all on the streets. He was wonderful. He said acid rain was kind of tricky to study so maybe we should pick something that is difficult, but not impossible, for a high school project. He suggested studying pollution in the rivers and I could easily see how polluted the rivers were. My friend Ginny joined me in the adventures doing this project. We got a small boat made out of rubber and air, and we floated along the river near my home in the snowy wintertime. You could see pipes coming in from a factory or from a town, and we would measure right by the pipes bringing (probably) some pollution. I ended up winning a trip to New York, to my first science conference. I really loved that experience, and my chemistry teacher who helped me so much. From there I came to Stanford, where I’ve had some more very good teachers.

Mentors, Friends, and Fieldwork

When I came to Stanford, I chose biology and I have had some really, really wonderful mentors. My main mentor has been Paul Ehrlich*1 and he is still in my field and leading a lot of the thinking in the area where I am trying to make an impact. And as I got further along, I also started working with Hal Mooney*2. They’d tell me what to do and then I’d try to go do it. I feel that most science proceeds that way actually, that we all stand, in English, there is an expression ‘Standing on the shoulders of giants.’ So I have come along at a time when some of the ideas that Prof. Ehrlich and Prof. Mooney had and promoted, now the world is more ready for those ideas and I can help advance the ideas.

Also, one of the big influences on me when I was a student here starting out, was living in the International House. With friends from all over the world, I developed a deep international perspective knowing and caring about the problems in the world, on a personal level. I later was able to visit the countries that my friends were from, in Africa and in Latin America. I have always been inspired by knowing those people from back when I was a teenager. And it was lucky that I met a really great guy there. (He, Gideon, was five years older and we became good friends. And then many years later, after he moved to Europe, he came back to California for a visit and looked me up and said ‘hello’. It was fantastic seeing him again. I knew I was in love. We married in 2000.) Back when I was a university student, I had a lot of other activities. I worked a lot to help pay the university fees and I was on the soccer team, field hockey team, the downhill ski team. I loved that.

At stanford University, 1991

In the University, I was able to do field work in Colorado in this beautiful mountain laboratory at about 3000 meters elevation and study the basics of how nature works. Sort of the machinery of nature, of our life support systems. After that I was able to start working in Costa Rica. In both places the idea was to understand one piece of the earth’s system in a lot of detail and hope that we could learn lessons from knowing one place or two places very well, for the whole world. So I have spent many years in those places and in Costa Rica I have worked for about twenty-six years now, trying to find out what kind of life will survive human impacts.

*1 : Ehrlich, Paul R. (1932- ) Biologist who pointed out population explosion's implications for the environment. Blue Planet Prize laureate in 1999.

*2 : Mooney, Harold A. (1932- ) Biologist who provided objective measures of how plant ecologies are influenced by their environments. Blue Planet Prize laureate in 2002.

Learning from Failure: Countryside Biogeography

Las Alturas Research Station, Costa Rica

When I started working in Costa Rica, the thinking was that the future of biodiversity depended completely on protecting natural habitats. In most places, most natural habitat has been destroyed, so the focus was on the remaining small patches of it: like Noah’s Arks, they were crucial to wildlife. Research therefore focused on islands of habitat: how many islands are needed to maintain biodiversity in a region. How big should the islands be? How connected should the islands be? The perspective was very much about habitat islands.

So, in 1995, I planned a study about islands of remnant rainforests, surrounded by a "sea" of farms and pastures in Costa Rica — and the study went completely wrong. I was putting out some commonly used feeders for little hummingbirds, and the feeders had sugar water in them and that attracted hummingbirds — and, on this day, also a big swarm of killer bees. These very dangerous bees can kill if they sting you. So the farmers — my friends - where I put these feeders were very upset. We had to remove the feeders and end the whole experiment immediately. Then I had no project. I went to Costa Rica, I had all these assistants. We had prepared a hundred feeders in a complex experiment and suddenly I had no plan, no equipment for another type of project.

We were mostly focused on the islands of forest, and their value for biodiversity, and I now had to think of something else very quickly. It is very difficult to survey biodiversity in tropical rainforest — and the feeders would have helped by attracting the birds that are normally very high up, bringing them down to a place where we could see them. So I then thought that I should look outside of the forest, on the farmland, because one can see the birds and other animals and plants more clearly there. In the forest, you really have to hear and just use hearing to tell which birds are there because they are so hidden in the leaves, and often so high up.

Royal Flycatcher on farm in Costa Rica

So I went out on the farmland for my new project and I couldn’t believe how many different types of bird we found out there. Much more than we expected. Then I thought that we are making a mistake to focus only on what we see as the islands of habitat. The birds don’t seem to see them as islands. The birds are flying all over, in the forest and out on the diverse farmland, eating and nesting. I realized that the farmland is habitat. Actually, we found many birds thought to be "rainforest birds", even the Royal Flycatcher in the photo here, in the farmland.

Published in 1997

So we developed a whole new approach called Countryside Biogeography. The new perspective involves looking at all of the different land cover types and seeing how much biodiversity can live in these different types — and then we can get to the farmers and managers and decision makers and say OK and work together. We should think very carefully about all of the different habitats that we could use to support conservation and biodiversity and human wellbeing. In much of the world, the best habitat is farmland.

Today most wilderness under conservation is less hospitable to people — maybe too dry, or too rocky — that is why it is still wilderness. What we need to protect now is where people live, because many of the benefits from nature come to us locally. In the human-dominated farmland or countryside we need more complete understanding of where nature is and of how we can harmonize people living in villages or on farms together with nature.

Economics saves nature

I really got to wake up to economics when I was a graduate student. If we could develop the case — make a compelling economic and business case for nature conservation — then we would change the world. During that time when I was a graduate student, Partha Dasgupta*3 came for a visit, a year-long visit here. I was really lucky that my mentor Paul Ehrlich organized a lot of meetings and informal dinners and occasions just to talk in a relaxed way. Normally when two fields come together, and in this case the fields were kind of at war, Ecology and Economics, there would be a tough problem getting to know one another and really coming to a level of trust where we could design new ways of thinking and of approaching problems. Partha was here for a year and here, I also met late Kenneth Arrow*4, who won the Nobel Prize in Economics. They were focused on developing a kind of science foundation for valuing nature — and much more than that, really bringing ecology into understanding of economic systems and decision making.

With her sister in W Germany, at 22

*3 : Dasgupta, Partha(1942-) Economist who brought together development economics and environmental economics in an effort to alleviate rural poverty in developing countries. Blue Planet Prize Laureate in 2015.

*4 : Arrow, Kenneth J. (1921-2017) US economist, the youngest winner of Nobel prize for economics at the age of 51.

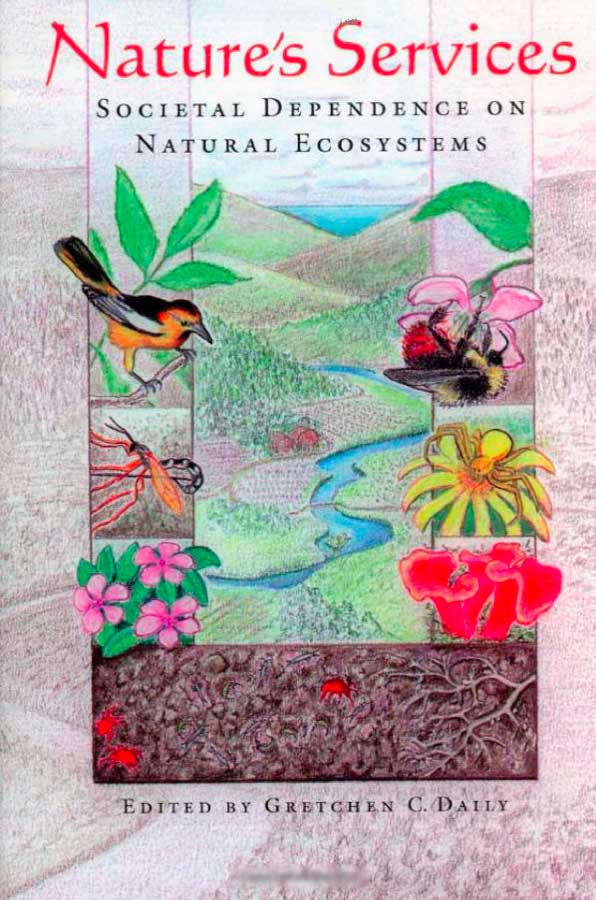

An influential book that made a first coherent case for saving the planet with cash

And around the mid 1990’s in the United States, there was a shift in the government away from the environment. It was clear: ecologists must do a better job explaining why we need nature. So the idea in writing this book Nature’s Services was to bring forward in a very systematic way what the economic dependence of people is on nature. The idea of seeing ecosystems as natural capital, generating a flow of services, is basically a way to connect with economics. It was to connect with politicians, with policy makers, with opinion makers. Peter Bing, Stanford’s longest-serving board chair, became a huge influence on my life and thinking at this time, helping me see how to connect with the real world.

And right at that time, New York City made a big decision that did help to change the way people thought. They had a problem with drinking water quality that was going down, so that water was becoming unsafe for the nine million people living and working in New York City. They thought ‘OK, we will build a big filtration plant’. But the price of that was estimated to be six to eight billion dollars. It was a huge price and annually it would cost a lot to run this plant, some hundreds of millions of dollars.

They didn’t know even in a wealthy city like New York City how to fund this. At the same time some environmental groups were saying actually the water of this city is famous for being clean and healthy and we could go back to how we have always maintained the clean, healthy water and restore the forest and the wetlands up in the agricultural areas where the water comes from. And they estimated that would cost only one to one and a half billion dollars. So it was on that argument, an economic cost/benefit argument, that New York showed the world that investing in natural capital could be a better investment than physical capital. Obviously, all through history we have depended on natural capital for clean water, but we have kind of lost that in the last decades of development with more and more focus on technology as the answer.

Nature’s Services was a book inviting many leaders in many different fields to shine a light on the broad range of benefits that we get as a society and as individuals from nature. We want to shine a light and start bringing these natural values into the dominant economic cost/benefit framework, and start changing that framework.

Criticisms and hope

Some people within the area of conservation were opposed to the idea that we could protect nature outside of wilderness. And I understand the worry - there is so little left and we must act rapidly. But at the same time, many countries are actually degazetting parks. And the number of protected areas is too few and they are too small and too isolated to make a big difference in human wellbeing, or in stemming biodiversity loss. So, we have to engage in conservation in the thick of human activity, where people are competing over land, over water.

To do that we need nature to stand up in economic, health, cultural, and other terms. And to do that we need to explain in a clear and inspiring way, why nature and how nature is so valuable. I think that we can start bringing nature into the equation. On the one hand I actually feel very worried about the future because there are so many dangerous trends at play today. But at the same time, I feel optimistic that people are waking up. They are seeing these enormous values. If we can create a universal language for talking about the values of nature, and if we can create a shared common approach for quantifying those values in a very systematic way, then we can shine a light on them and bringing them into decision making in a meaningful way. Then I think we will see this transformation turn into more and more of a revolution and drive the change we need.

From theory to Practice: Natural Capital Project (2006 - )

We knew that scientists alone would not get very far and so we started the Natural Capital Project with many, many others. The idea was to do three things. First was to work with decision makers to understand what problems that they needed to solve. And how could we bring nature into their world of problem solving. Then the second was to develop simple software tools to make science accessible and actionable. If I’m in charge of development in my country, I would ask where should I invest in nature? Where do I most need nature to achieve my goals? Where is nature providing really important hidden benefits that I must be thinking about to achieve my goals? It would be a practical software system that answers decision-makers’ questions. Then the third main aim was to make this go global, and mainstream, and to drive regeneration of nature, while human communities also thrive.

With the Natural Capital Project team

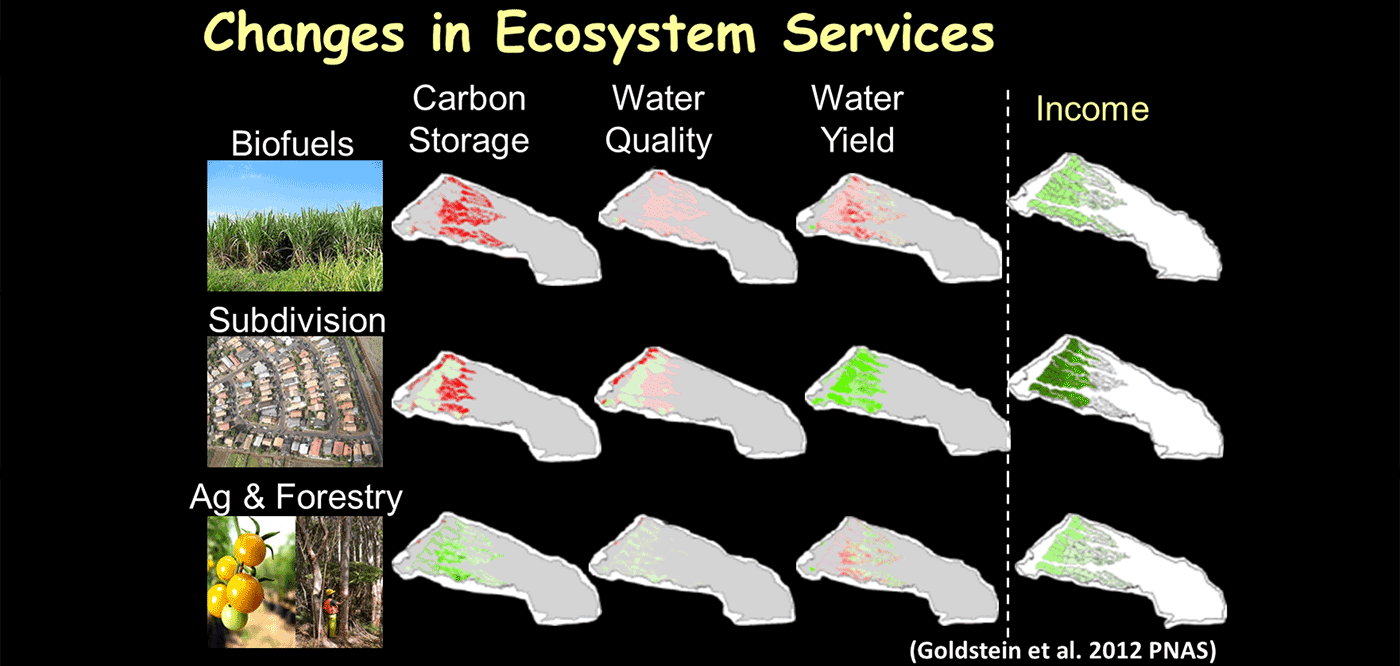

Innovative mapping software: InVEST

At the beginning of the Natural Capital Project, we realized that a key missing piece was being able to show someone on a map where nature’s values are. Where that city is drawing on nature, for example on forest for water purification and storage, for drinking and irrigation, and all the other benefits people get living in the city, like cooling. We thought that software was the way to make it possible for anyone to play around on a computer very visually. We put maps out on a table to think together about planning, think about the future under different scenarios. So in the past, people would tend only to look at water then at transportation, then at some aspect of health then at farming. We wanted everything integrated, and so the system brings all the science together and all stakeholders together, letting values become clear in the picture, and opening ways of cultivating shared values.

Green indicates increase over planning horizon, red deficit.

In Hawai`i, we had our first chance to make this possible, co-developing the InVEST software. It came at a very important time when Hawai`i was experiencing crisis. There is only a few days’ fresh food supply on the islands at any one time and very little agricultural land left. They import most of their energy as well. So a question arose with the largest private landowner in Hawai`i, Kamehameha Schools. Balancing different values in their decision making over how they use land, in a particular 10,000-ha landholding shown here called Kawailoa.

Kawailoa, O`ahu, Hawai`i

We talked with many people, and used InVEST to map out their alternative visions of the future for Kawailoa, for the three scenarios (sugarcane biofuel / housing / agriculture and forestry), how much carbon change there would be, how water quality would change, how the amount of water would change and then what the income implications would be. The overall result was that while having the lowest income, the agriculture and forestry option proved the better balance across those objectives. They actually won the American Planning Association’s 2011 National Planning Excellence Award for Innovation in Sustaining Places.

Today the InVEST software has been used in basically every country (>185 countries). Over the past ten years, we have developed the basic tools and we have developed many compelling demonstrations that show how you can achieve win-win outcomes for both human well-being and for conservation of nature, our life-support systems. We have done that in about sixty countries directly, and also with numerous companies operating in different parts of the world in agriculture, in mining, in infrastructure, in hydropower — across many sectors.

Biggest Opportunities in China

Presentation at Stanford, to high-level Chinese officials, 2017

The Natural Capital Project is focused on countries all over the world. We have one of our biggest opportunities today in China. That is partly because that there has been great crisis in China. Some of the worst flooding in history happened in China in 1998. That opened more awareness on the part of government leaders of the value of nature. The flooding was caused partly by massive deforestation in the upper mountainous areas of the Yangtze River.

And China started investing back in the year 2000 in forest conservation and restoration. So the opportunity came to the Natural Capital Project to help design a system for looking at the return on investment of those major efforts in China to regrow and protect the forest. The questions policy makers were asking were, did this do a good job? Are we more secure from flooding today? Are there any other benefits that came from planting and protecting so much forest? If we think into the future, where do we need to protect more and how much do we need to protect more?

So we launched a study together with an amazing scientist, Ouyang Zhiyun of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, together with the Ministry of Environment and other key institutions in China. That looked at the ten years from 2000 to 2010 and we mapped across the country exactly how the ecosystems were doing, the forest, the grassland, the desert and the scrubland. All of the ecosystems got mapped, and the cities, and we looked at the change in that ten years to answer the policy makers’ question, ‘Did our investment pay off?’ It was amazing to see with the InVEST software that the investment did pay off for the five priority ecosystem services. Those are flood control, sandstorm control, and water supply for drinking, for agriculture, and for hydropower production. Another is land productivity for farming - actually for all the benefits that we get from land. Then the fifth service was carbon sequestration.

I felt, you know, we really had a story to tell. If a place like China that has been so focused on GDP growth and yet has now seen what the costs are, the huge costs of pursuing GDP growth only, if a country like China could see now actually that investing in nature is paying off in key ways that the government cares about, maybe we could develop lessons for lots of other places. The one worrying finding though, was that biodiversity is still declining in China. That actually wasn’t surprising. We know it takes a long time to restore suitable habitat. You cannot just put one tree out and expect that a panda bear is going to come walking over and re-inhabit an area. It takes a long time to restore biodiversity.

The government took notice of this finding and the government has now committed to developing a much more comprehensive and much better funded and strengthened national parks system. The Natural Capital Project has helped do the analysis of two things. One is where to put the nature reserves. Where in the country would you secure the most biodiversity? Then the analysis. How can we integrate people who live everywhere in China, in the wilderness areas and everywhere else? How can we integrate livelihoods with conservation efforts? That was where we could identify two types of reserves that will be created. One type will be for the most sensitive biodiversity that really needs little human impact in places where not many people live normally.

Nature in China

Government funding will protect all of the values and the options that come from saving those special places and species. Then a second type of reserve is one often with more people and human activity. As long as it is not hurting the key nature’s services and as long as some biodiversity can thrive in those places, then there will be payments made for the services and for the biodiversity that benefits locally and regionally.

More recently, in 2021, NatCap approaches have been standardized in climate resilience planning across the Caribbean (through the InterAmerican Development Bank), and in securing ecosystem flows in China, where 51 percent of land is now zoned for regeneration and 200 million rural people are being paid to do it. These investments are increasingly coordinated using Gross Ecosystem Product (GEP, advanced by Ouyang Zhiyun and other Natural Capital Project colleagues). GEP is a framework and statistic like Gross Domestic Product (GDP) — but focused on the value of goods and services from ecosystems — and it was recognized in 2021 by the United Nations Statistical Commission as a tool for global use (UNSD 2021).

The Future

So my next mission with the Natural Capital Project is one shared among the many partners about two hundred and fifty around the world now. Our next mission is to scale up and mainstream what we are doing. The second arena is in urban development. More and more people, over half of humanity live in cities today. Suppose to be seventy to seventy-five percent by 2050. Cities represent maybe the biggest risk to the human future in how people living in them are becoming so detached from nature today. Cities also offer the greatest opportunity to tune our planning and our management, to recover nature and connect more people in cities with nature. In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic and extreme climate events opened greater recognition of the values of nature, especially to city residents. So we have the understanding at the level of health — physical and mental — and also at a very basic emotional level, and in the way we think. We plan to advance our data and software platform and to deliver the information that decision makers and investors need — for planning human development across countries, and especially urban development, in this next ten-year period.

To every child in the world

I ask myself a lot ‘Why am I working so hard to make this change in the world?’ because it would be much easier in my family life and in my personal life to just enjoy the biology. I ask myself ‘Why do I work so hard?’ especially trying to change policy. What keeps me going I think is two things. One is recognizing that we are at this moment really of — it’s an unbelievable moment in the history of humanity — where it is possible that we enter a future with tremendous suffering and tremendous destruction of the planet. Yeah, we need energy. Yeah, we need food. There are a lot of needs we have, but how do we balance those needs with the underlying need to secure nature? There were not so many of us throughout human history. We didn’t have such incredible technological power. Today we have many more people, we have much greater impact per person, and the power that we have unleashed we have no control, or very little control over. It is very scary to think how little control we have over some of the power we have created through science and technology.

![her daughter Carmen[left] and son Luke[right]](int_img/luke_carmen.jpg)

her daughter Carmen[left] and son Luke[right]

My dream is a world where every child can get out and play in nature. A world where everyone has the opportunity to have all of their basic needs met for health and wellbeing, and to develop their own potential in a way that they can contribute to society. It is a world where nature and people thrive together and where that connection is made much, much stronger than it is today. I always feel so bad leaving my kids and my husband back at home. In conservation, you really have to go out to different places around the world to have any understanding. Fortunately Gideon, he understands all of that. We talk about our work quite a lot. He also tells me when I’m just talking nonsense or being confusing, and helps me be focused. At the same time I tell my kids, you know, we are saving nature, we are doing this together. I hope they have an understanding of why I am away and how we hope to leave a world that is just full of nature and full of opportunity for kids everywhere to be able to see the beauty of the earth and to realize their own aspirations in their own life and have the health and security that we get from nature to make all of that possible.