A Better Future for the Planet Earth

Hans J. Schellnhuber Interview Summary

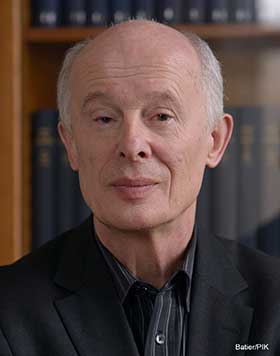

Prof. Hans J. Schellnhuber (Germany)

Physist,Born in Bavaria, Germany (June 7th, 1950)

Founder and Director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK)

Childhood

I was born in 1950, five years after the Second World War. I grew up in a small farm in the southern part of Bavaria. They were farmers on one hand, but my father was also working in construction sector, as a self-employed person. Always in those times we had to have two or three jobs to get around, to really make a living for your family. And my mom was a sort of a nurse before, but when the children were born she had to take care of the family.

Although materially we were not rich but culturally we were pretty rich. My grandfather was actually the mayor of the town and my granduncle, who was a historian, wrote down the history of the town and the whole region. There was a lot of talk about history and even politics and arts and so on. I recall that we had endless discussion about the state of the world and these things. What I recall really in particular is my mother, I was very close to my mother, and I kept on asking her questions, "why this is so and that", and she gave me explanations. Most of our family were very wise, I have to say.

Childhood

And, I had a wonderful life surrounded by forests and fields and trees. Alone or together with my brother I loved to sort of get lost in the forest near this town. Then I came late for dinner and it was dark already, so I was always told not to be late at home. If I look back in time, this was the happiest time of my life really.

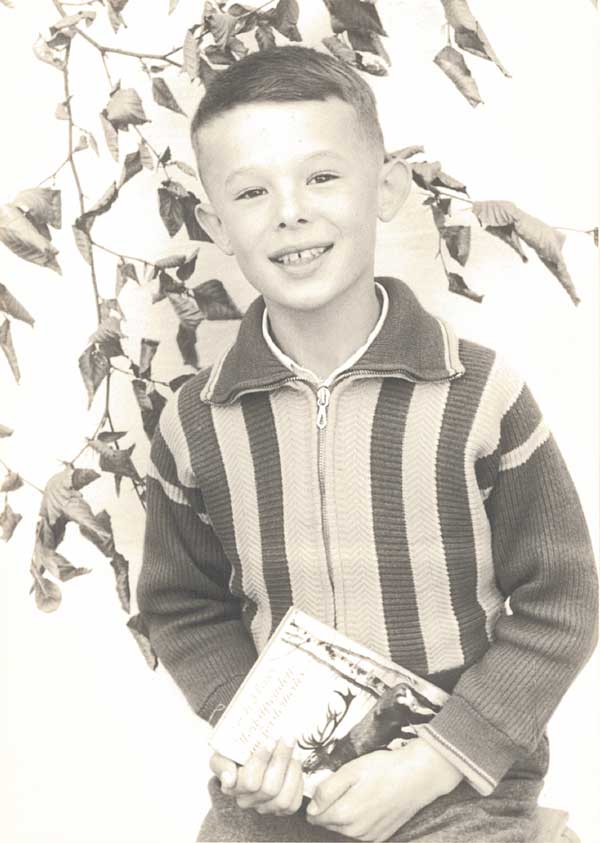

Gifted Student

Elementary School: at the bottom left

I was a pretty gifted student in a sense. I recall in the first year of school I was not interested at all and I think I just dreamed through the day, but after two or three years I discovered that I was able to do all the exercises and all the tests with no effort at all.

I started to read, just everything I could get hold of at the age of 9 or so. It was so lovely to dive into the fantasy world so I read things like geography, novels… whatever you have. In all my afternoon more or less, I went to the forest or to the field, with the nature, or I was just reading things. I really loved to just dive into the dream world or fantasy world.

On the way I read many things so I got interested in all types of subjects. I became interested in physics and things like that around the age of 10 or so. What is the universe made of, why are the stars you see in the night sky look like that, and so on…so together with my older brother, who is 3 and a half years older, we stared at the sky, for example. Then I started to read books about planetary systems.

Cuban crisis and Einstein

What is vivid in my memory is in the 1962, the Cuban crisis. That was really at the blink of self-destruction so I recall very well the time. I was really also focused on this nuclear arms race and things so on, what do we need to do to avoid the third World War. So I felt of reading Einstein. That was around 13 or 14, but I start reading Einstein not with the original papers but with a collection of his thought called "Mein Weltbild", means "my view of the world" in German. It's a collection of essays where he wrote about quantum mechanisms, relativity theory but also about his ideas about peace, political system. So it was a mixture of scientific insight, personal thoughts and political wisdom. I think that was a very good guidance to me.

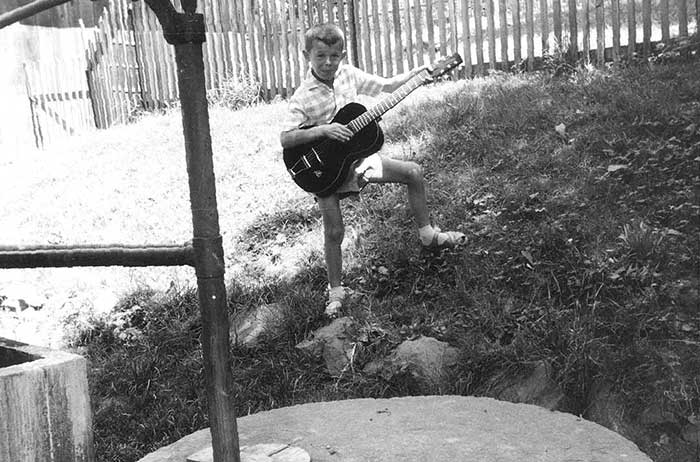

A boy in a beat band

And when the Cuba crisis was resolved, we were gliding into the rolling 60s so that means 1964 or 65. I was influenced by the music of that time. The pop music, the Beatles and all that came along, and theworld seemed funny, colorful, wonderful and peaceful,so this was of course a great time. Also in Germany everything came from the United States or England and so on.

An unexpected Christmas present

So yes, I was given a guitar by my parents, actually as a Christmas present. This was a real surprise…one of the very few surprises in my life. I was never expecting that because it was very expensive. So I immediately started to create a beat band with abominable name which was a complete nonsense. From the age of fourteen to something like twenty-one I played in bands. That was a lot of fun.

With the band members

If you are young, you are living in a parallel universes and you can accommodate everything at the same time. I was also playing at the football club, I did music, I did the secondary school…I read everything that was published in science fiction. And I took interest in actual science, and physics in particular. So this interest did not go away really, or even became stronger.

Entering University

It was, first of all, very unusual for our family that children would go to universities. That was not usual at that time. In the upper middle-class household tiers, of course did it, and for us it was the first thing, the first generation. So my elder brother was sent to university of Regensburg in Bavaria. But my mother told me "We have no money to send you to university." And at that time we didn’t get a good scholarship. "For you, sorry, you will have to take over the farm, there is no way for you. But there is one possibility." She told me like that. I recall very well the day and what she said…it was two years before I graduated from the secondary school. She said there is a very simple, very special scholarship for the highly gifted people.

If you score everything at the highest grades in school, then when you graduate, the final examination has to be, you must have 99 or 100 points from 100 points. So I said, "OK, I'll do for that." Now I really recall that…I thought "OK, if that is the only possibility to go to university I'll do that". And I actually did it. Bavaria had really hard examinations, then I got this special scholarship for the highly gifted, which was wonderful because…I was able to pick any university I wanted. So I went to Regensburg because it was close to home, and I studied physics and mathematics.

I gave up football and music at the university but I started to travel a lot, in particular during the vacations and so on.

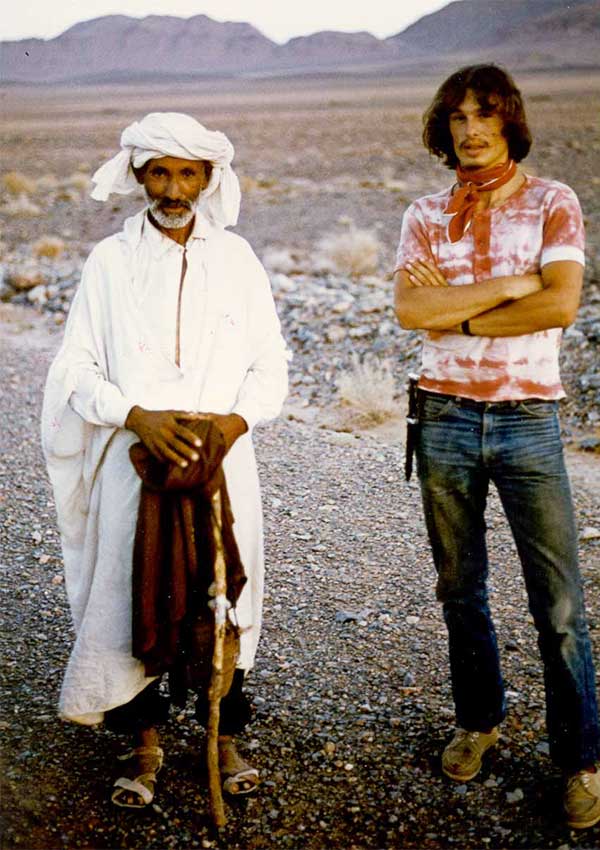

I travelled across Africa, for example, and it was a great adventure and great experience. Through the desert with the VW Beetle and I was also…I came across the great Sahel draught at that time that started in 1972 73… So I was, for the first time really, encountering environmental catastrophe.

In the Sahel

Studying in the US

I did my master thesis in a very complicated field in mathematical physics, but Ph.D. thesis was a really fundamental problem in physics. And then it opened the world to me. When I just finished my thesis and gave lectures about it, it happened…an old friend of my PhD supervisor, visited.

Gregory Wannier*1, who was a famous solid-state physicist, and said, given my success here with the thesis I should now go to the United States. He continued, there is now a new institute for theoretical physics called ITP at that time. They want to be a formal institute for theoretical physics in the world, and it has just been founded by the National Scientific Foundation and it would house just 80 people, many of them will be Nobel Laureates, and they have a few Post-Doc positions. It was time for the application process to be announced world-wide.

It turned out that I had an office on the 5th floor in Santa Barbara (ITP). And just across the corridor there was sitting a Novel Laureate who have explained the superconductivity, and John Bardeen, who invented transistor, which is the basis of the digital revolution, of course. He was sitting two offices down the corridor so whenever you enter the corridor to get a coffee you ran into a Nobel Laureate. These people were very nice and they said, "young man, what are you doing here, can you explain?" Then we sat down in the library…that was amazing, of course. So I was just lucky, you see. I mean... I just got into the eye of the hurricane, the intellectual hurricane, that is.

*1 : Wannier, Gregory H. (1911–83) physicist who made major advances in solid state physics,; born in Switzerland.

Chaos theory

The ITP was an institute for advanced study like the ones you have in Princeton. But the idea that you attract the best is people from a new emerging field. There was a group at that time on dynamical system or chaos theory. The pioneers of chaos theory were there, like Mitchel Feigenbaum and Benoit Mandelbrot who invented fractal theory and David Ruell. I was just sitting in the seminars and listening to that, but I was touched by the new development for me to from all sides. In physics, we had more or less almost the tyranny of linear thinking. So if you had a complicated problem the physicists would sit down and say, "How can we linearize it?" But it turned out that the really most interesting things are happening outside the linear domain. So I got really fascinated by that.

At the university of Oldenburg

After studying at ITP*2, in 1982, I went to the university of Oldenburg, in the northern part of Germany, because I was offered a good position there. I started to work on dynamical systems, chaos theory, fractal and so on. I tried to apply these things to complicated structures and the most complicated structures where you cannot apply chaos theory and non-linear dynamics and fractal geometry, all in nature actually. So just look at the cloud or a river system, a river delta. Then it turned out…yes my love of nature I always had from my childhood on, and my love for mathematical structures, they also joined.

*2 : Institute of Theoretical Physics, at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

At the university of Oldenburg

(Photo provider: Institute for Chemistry and Biology of the Marine Environment)

German reunification and foundation of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK)

We set up my own group in Oldenburg. And something happened, that is highly non-linear and completely unexpected…the German reunification. I recall very well that, I was in England and on the plane back to Germany. I opened a newspaper and saw the picture on the front page, people dancing on the wall, the Berlin wall. I thought, "What is this? It must be a fake!" Because I was somewhere tucked away in Cornwall in the countryside, we did some work, so I didn’t get the news until I saw this newspaper. This was a shock in a way but it was also fantastic information. This turned everything upside down in Germany as you can imagine. At first people moving freely between the east and west and it turned out… yes, there will be one German state again, a unified states, east and west. The whole eastern German scientific system, the academy of scientists, would be demolished first, the pieces will be reformed, and new institutes will be created. Then some people thought, "Well, if we create a completely new academic landscape in eastern Germany, couldn’t we do something new, instead of just reassembling the fragments. Why do we not found an institute for climate impacts research?" That idea was really a courageous move, because nobody was really worried about the problem until the 1980s more or less.

I was a young physics professor in Oldenburg and we have played around a little bit with issues like sea level rise and things like that. So I was asked whether I would like to come to Potsdam and become a founding director of that institute. So I looked into climate impacts, what does it mean, what type of research would it be, how you could organize that… And I felt, again it was a pure instinct really, pure intuition, like I felt with chaos theory that this is something that will grow into something really big.

PIK: aerial shot

PIK and Tipping points

In 1993, in the beginning of the institute (PIK), the thinking was very pedestrian. You look at potential impacts of the climate change, so assume the world warms up by 4 degrees or whatever by 2100, what will be the consequences, the impacts on…forestry, for example, on agriculture, on water resources. It was all about incremental change, 5% of changing wheat yield, for example, malaria spreading by a few percent of the original area and so on. And I found this not only boring but found it wrong habit, ill-habit. In a sense, we should rather think about the things we want to avoid by all means, things that must not happen, while we warm up the planet. So in the end I decided not to run an institute only for climate impact research. PIK must also research how climate changes comes about, what are the consequences and what can be done about it.

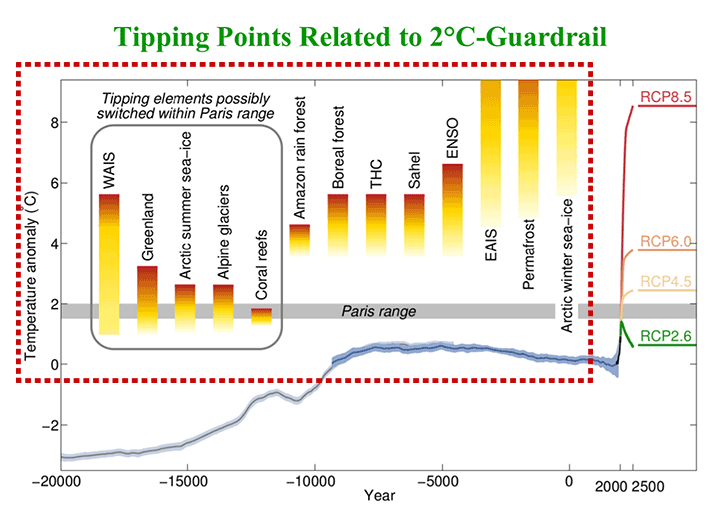

So why do you want to stop global warming, for example? Why should we stop it? Because we want to have our country safe? OK. But if you say "safe", then we all have to think, what are the risks you run. Global warming is based on how we use of fossil fuels, but it created the modern world. If you switch from one industrial metabolism to the new one, that may cost billions and trillions. The benefit is you have to avoid existential threats. But is that really true? So we were trying to find out what is it we need to avoid. And later I came up with an idea together with my colleagues, of tipping points in your system. So it could be that Gulf Stream could be shut down, or the great ice sheets would be melt down, and so on, if you change the global mean temperature by certain degrees.

The first insight was that we should keep our system within the tolerable window, that means in particular we should not warm up the planet by more than two degrees centigrade*3, so that was the beginning. And if it would happen, while we warm up the planet, we must not warm up the planet that much. That was the idea.

For example, if the temperature rise exceeds 2 °C, "WAIS /

Western Antarctic ice sheet" Melting (a left orange bar) occurs.

*3 : compared to before the Industrial Revolution.

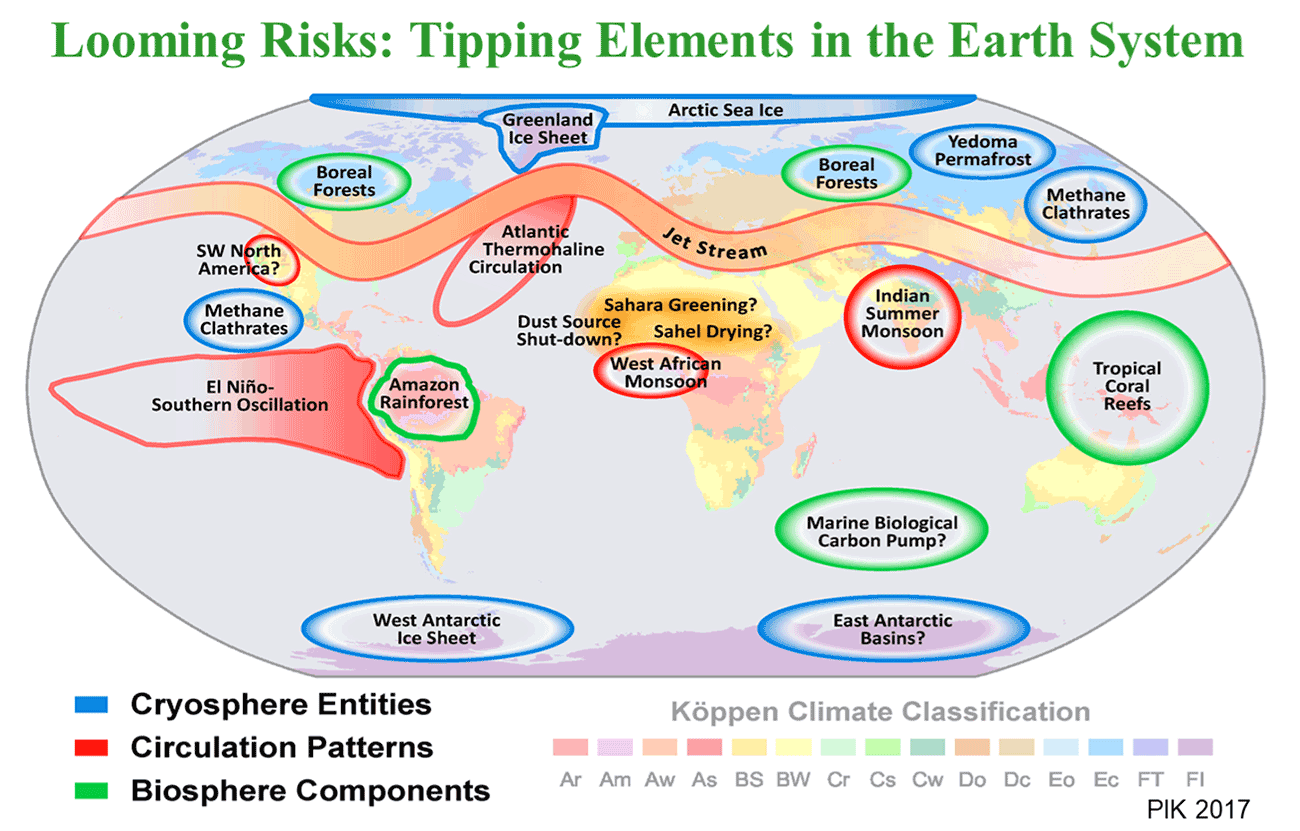

Tipping elements

So I came up with the collection of 10 or 12 of what we call tipping elements. These are defining big crashes, the big accidents we could encounter if we keep on warming the planet. So in a way my connection and my understanding of non-linear dynamics, made me able to explore this research field. For example, when Stefan Rahmstorf joined my group in 1996 here, we have done a lot of work on, in technical terms we called, "Thermohaline circulation", sort of better known term is "The Gulf Stream System". That is very important for Europe. For Japan, the "Kuroshio" current is very important, which is providing more or less warm water to Tokyo all year along, so that’s why you have this very humid and warm climate. The Western Europe benefits tremendously from so called Gulf Stream, which is coming from the Gulf of Mexico, it’s a warm current across the Atlantic.

Gulf Stream or Thermohaline circulation really starts to form the coast of Greenland. You have very salty, cold and dense water sinking down to the bottom of the Atlantic. And this is creating what we call the conveyer belt, which goes around a vast part of the planet actually. Now comes an interesting story. If we warm up the planet, the Greenland ice sheet, which is 2,000 meter thick, may start melting. So if you heat up the planet by 3 degrees it cannot be regrown, so to speak, for 10,000 of years. If you dilute this cool, salty, dense water by fresh water from Greenland, the motor is stopped for the water would not sinking anymore. So the global warming can create so much melt water, that the Gulf Stream can be stopped. That is a highly non-linear accident. You cannot calculate it in an incremental way. During the Glacial time, the Gulf Stream got shut down many times actually, so completely collapsed. And it became much cooler here in northern Europe.

And you can compare it in a way to the vital organs in human body, like the heart or the kidney and so on. Most part of our body are not really important, I mean…if you cut your skin you will not die from it. But if somebody puts a needle in your heart you will die. That's precisely the same in the planet. Each tipping element is the eye, the heart, the kidney, the lungs, the liver…of the planet. And they are prone to highly non-linear responses if you change the global mean temperature.

Change the discourse of climate change

At first I thought it was extremely important to change the discourse of our climate change. Because at that time in the beginning was just, "we are emitting CO2, this will change the climate and it will warm up." But people did not think about what are the things they want to avoid, like melting down Greenland. So I turned it around, not only me but together with a number of colleagues. We turned the discourse around and said, "Now, what we want to avoid by any means more or less is the melting of the great ice sheet, because it would mean the sea level rise of, 10, 20, or even 70 meters in the end. That means the most of the coastal zones would be lost. Many of them. So this has to be avoided all means." If we apply more energy efficiency, if we have a carbon tax and so on, then the emissions will go down from twenty billion tons a year to, fifteen maybe, which led ultimately to the idea of carbon budget and so on. So I think first of all we changed the discourse and ultimately this had the major influence on the Paris agreement.

In Paris, what is not decided is that the world must not emit more than…say 40 billion tons of CO2 per year. But we have to confine global warming to well below two degrees. That is now international law. And this was, I think, heavily influenced by our discourse so to speak, on tipping points and so on.

Meeting at PIK

We have Only 3 years left

OK, what are we going to do about it? Because now you can calculate two degrees. We have a carbon budget left for humanity probably about 600 billion tons of CO2. This is our credit left with nature. If we spend this credit and overspend it, then we will go beyond 2 degrees and we will enter the world which is incalculable, more or less. I mean, simplifying things. In 2016, 2017, we have already spent close to 40 billion tons of CO2, and that would just go up under the normal circumstances.

We need definitely to peak the emissions so to bring them to a turning point actually by 2020. So we have more or less 3 years left to start saving the world. We have to steadily decline, very quickly, and actually by 2040, 2050 we have to get rid of emissions from industries and so on completely. So that means, 3 years to turn the tide, and 3 decades to save the world. So that sounds dramatic, but it's the truth.

What are we going to do?

So what are we going to do? We have to spend the carbon credit left, 600 gig tons in a very wise way. And ideally, we would ask the richest and the most innovative countries in the World, Germany, Japan, or the US, to spend only the small part of it and leave the huger part of it to the developing countries, who does not have even access to the electricity for example. On the other hand some of those countries can leapfrog. In Africa you do not have to duplicate the development of the Europeans or Japanese infrastructure, you can directly jump onto the solar bandwagon, for example.

With Angela Merkel

But ultimately I think it's an individual decision. So if you buy a product in a department store you should know what the carbon content is. Does it come from 10,000 miles away, does it… have been produced a lot of CO2 emissions? Was it grown in an organic way or by industrial agriculture, a lot of water is wasted, and so on…So if you, as a consumer, make the right choice and you also try to lead the lifestyle that is less carbon intensive. You set the standard for it, and even the biggest company come down on their knees if they are deserted by their consumers. So I guess choosing a carbon-friendly lifestyle, making the right consumption choices, and also voting for policymakers that do favor climate action, so in our own sort of limit it is our choice to make. I think the only way the world can be saved is through global social movement, a social movement for climate protection. That's the ultimate dream.

As a scientist

We, scientists should not only find the truth and invent great things, but should also think about the consequences, the impacts of our inventions and innovations. We are responsible of the creatures we put into this world. This was not seen by the most of the physicists in Germany before or just after the War. The scientific community said we are completely able to invent weapons of mass destruction but we have nothing to do with politics or whatsoever, we are not really part of the society. Give us money, let us play, then we will invent wonderful things but it is not our responsibility what will come out of it in the end. Now I am saying this because, I had an encounter with the similar problem in a world of climate change. Yes, we scientists come up with wonderful inventions, for example how to suck up carbon from the atmosphere, we can dim sunlight to cool down the planet. But we cannot leave this just to politicians, we cannot just invent something and say "We have invented it for you, we have no responsibility."

So when you study climate change, you have to think about your role in the society and your special responsibility like Einstein. Because, I know more about the climate system than probably most people in the world. Much more, actually. And the nuclear physicists at that time knew much more of an ordinary citizen about the threats and opportunity. So if not, who else than the experts have to take responsibility of that.

Message

I have written many studies but also a book in German which is more or less also an account of my life. So it starts with my youth and talks about my development as a scientist and in the end also my way into becoming a public intellectual. When I talk about it, people keep on asking me, "Don’t you get completely depressed or frustrated?" And so there are various answers to it. Actually it depends, sometimes you wake up in the morning and you feel really depressed. What is cheering me up is when I look at my little boy, who is 9 years old, and I just think…I mean, I must not fail my son. You must not fail your children. You must not fail the future generations. You receive so much from them and you have to give actually the little thing, that is, the world that their lives are not worse than our lives. Let’s give them the same chance at least, as we had in developing our own lives. I think it's a very little present you give to the future generations, that you hand out for this planet in a states which is at least not worse than the states we received it. I think this is not demanding much really. You are not even asked to improve this planet, just not to make it worse.

His latest book

With 9 year-old son

As long as I know for sure that there is a chance to save the world. As long as at least there is a slim chance to keep global warming to manageable level, I just have to do it. I have to go for it. Could you really say, with all the wisdoms we have, the insights, there was a slim chance in the year 2017 to save the world but we were not ready to take it? Can you imagine to do so? It's impossible. You have to go for it. That is our responsibility. My generation in a way was a golden generation.We were born after the world war, we enjoyed the rolling 60s, we enjoyed globalization with all the opportunities. The least we can do is to make a little contribution to saving this world.