A Better Future for the Planet Earth

Jared Diamond Interview Summary

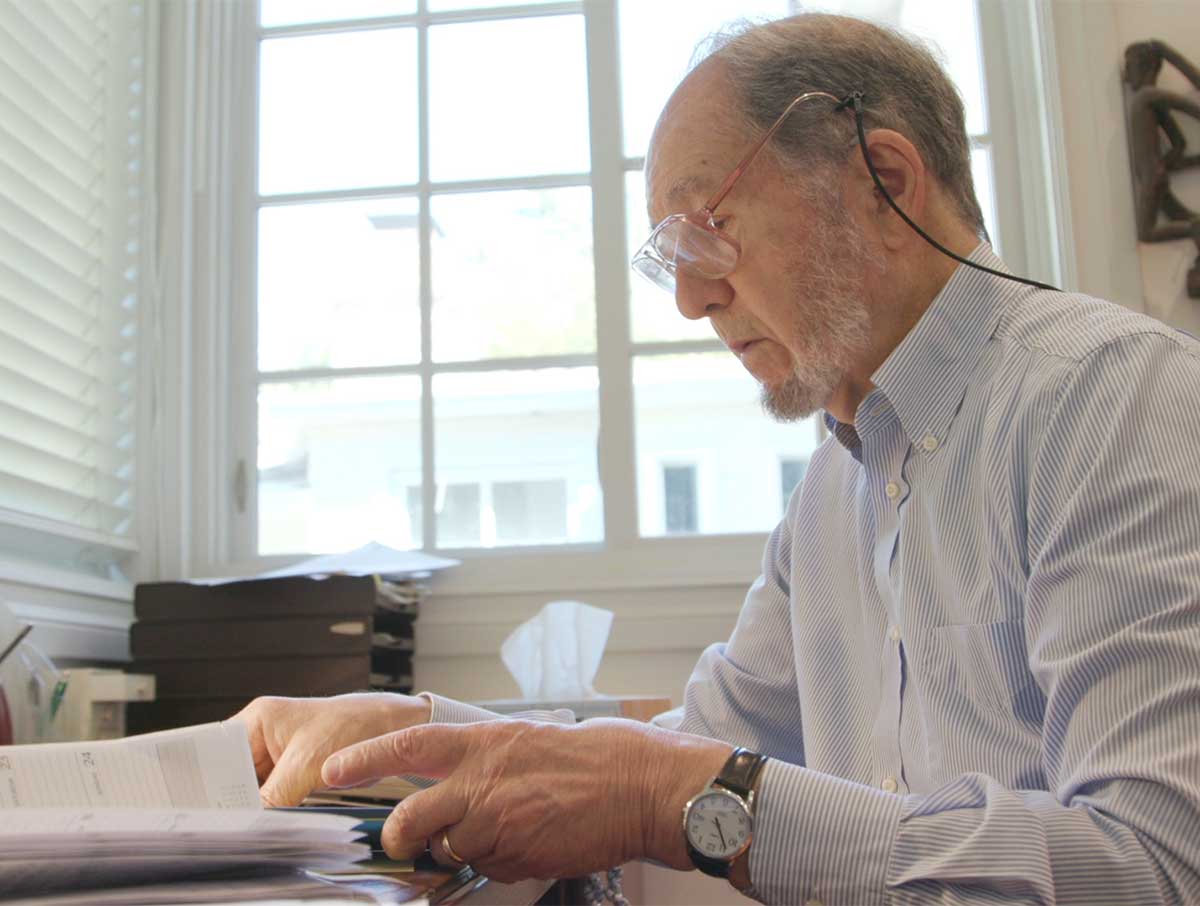

Prof. Jared Diamond (USA)

Evolutionary Biologist

Physiologist, Biogeographer,

Ornithologist, Historian, Author

Born: September 10, 1937, Boston (USA)

Professor of Geography at the

University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA)

Childhood

Early Childhood

I was born in 1937 and grew up in the city of Boston. My family consists of 4 of us; myself, my father, my mother and my sister who is one and a half years younger than me. Both my parents were the children of immigrants and lived in New York, but then moved to Boston before my sister and I were born. My father was a pediatrician specializing in childhood blood disorders at Harvard medical school. My mother was a pianist, linguist and school teacher. She taught me how to read when I was 3 years old, and I began to play the piano when I was 6. Having seen my father working as a doctor, when I was asked what I wanted to do when I grew up, as a child it was just a natural thing for me to say that I want to be a doctor like my father. So it was my father’s influence that led me into science and medical research.

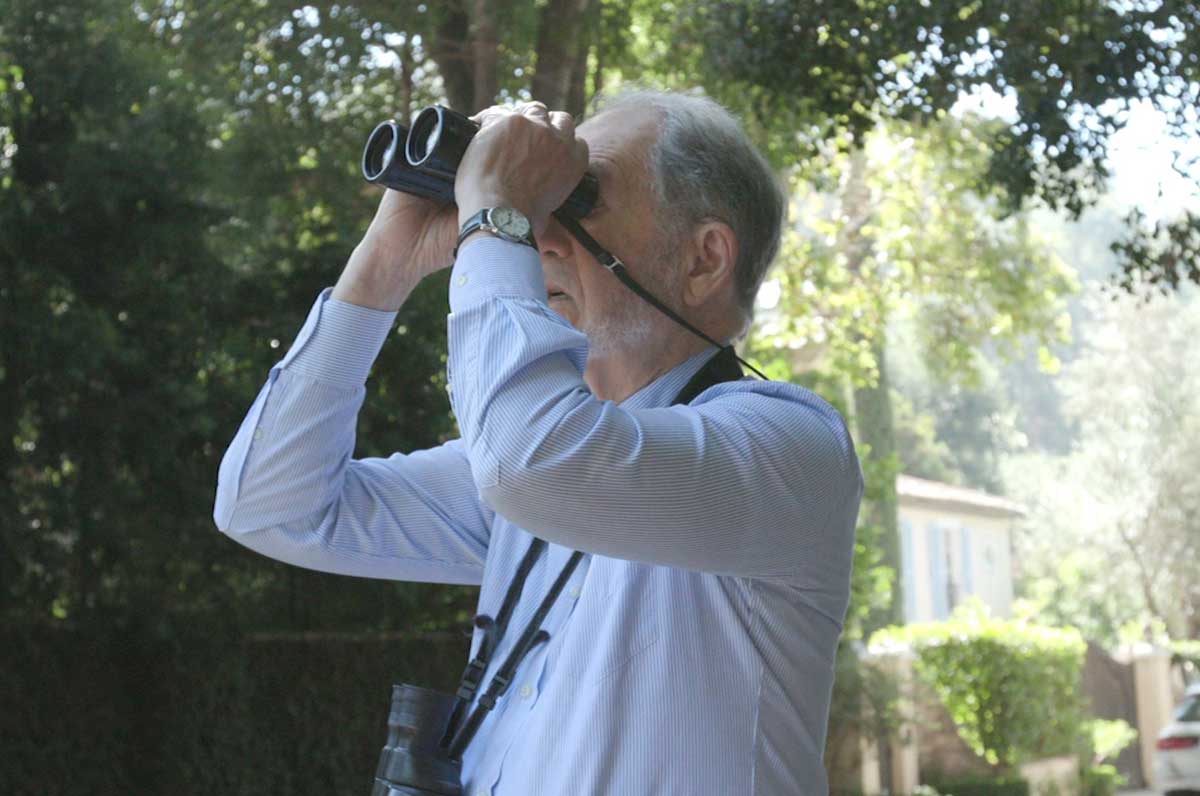

When I was a child my hobbies were reading lots of books, collecting stamps and playing the piano. I was quite serious about music. One of my other hobbies was observing birds. When I was seven years old, I suddenly got interested in birds. I could distinguish several types of birds while watching them from the window. Boston is a big city but my family spent our summers in the forests of New England, in New Hampshire and elsewhere. I became familiar with the forest and started to observe birds. That is how I got into birdwatching which I continue to do to this day. Birds are active during the day unlike other animals, and can be located by their singing. Birds also depend upon sight and sound like we humans, unlike most mammals that depend on the sense of smell. So, we humans can understand birds better than other animals.

Prof. Diamond’s parents

Interest in Diverse Fields

Middle School and High School

I went to an all-boys school that specialized in teaching Latin. So, I learnt many different languages such as Latin, Greek and French in school. It was my mother who was a linguist and a teacher, and this school got me started in languages. Since my teenage years I have read a lot of short stories in Latin, Greek, German, Spanish and French. I also had a wonderful history teacher in high school, so I became interested in history as well. Of course, I was also interested in science because of my father. Literally I was interested in everything, and ever since then I have remained interested in everything. Most of us were interested in many things when we were children, but as we grew up we were told that we have to concentrate on one thing, one job and not be interested in anything else. I was fortunate that I was encouraged to continue to be interested in many things. I also enjoyed explaining things to my younger sister; about birds, how to pronounce a word and what she should eat for dinner, just about everything. I believe that it guided me to what I do now, writing books and explaining things to people.

Medicine, History, Geography and the Environment

University and Postgraduate School

I graduated Harvard University in 1958 and in the following year entered graduate school at the University of Cambridge to study gallbladder function and obtain a doctorate in physiology. The reason I chose to study the gallbladder was simple; that I’m terrible with my hands. In school when all of us had to build a simple radio, I couldn’t even build one properly. The gallbladder is a simple organ that does not require complicated equipment. But there were times when my research was not going well and I almost gave it all up. But with support from others and advice from my father, I gradually produced some good results and obtained a PhD in Physiology. After that I continued my gallbladder research at Harvard Medical School and eventually decided to follow a path in science instead of medicine.

During my years of university and postgraduate study in physiology, I became interested in history and geography, which defined my career path. As I was studying at Cambridge University, I thought I should try living in another part of Europe outside England as well, and stayed in Germany for a while. The reasons I chose Germany were that they have the best beers and wines in the world, the music, and the biggest reason of all was that I could climb in the Alps. During these four and a half years in my early twenties I talked with many friends in England and Germany and learned very quickly that my European friends have had very different lives from mine as the result of their history and geography. I grew up in the United States so I was not directly affected by World War II and we were not bombed, but it was not the case for those who lived in Europe. They were either directly affected, orphaned or their father had been imprisoned, and that made me realize how major historical events can have a big effect on one’s life. So, these experiences reinforced my interest in history and geography.

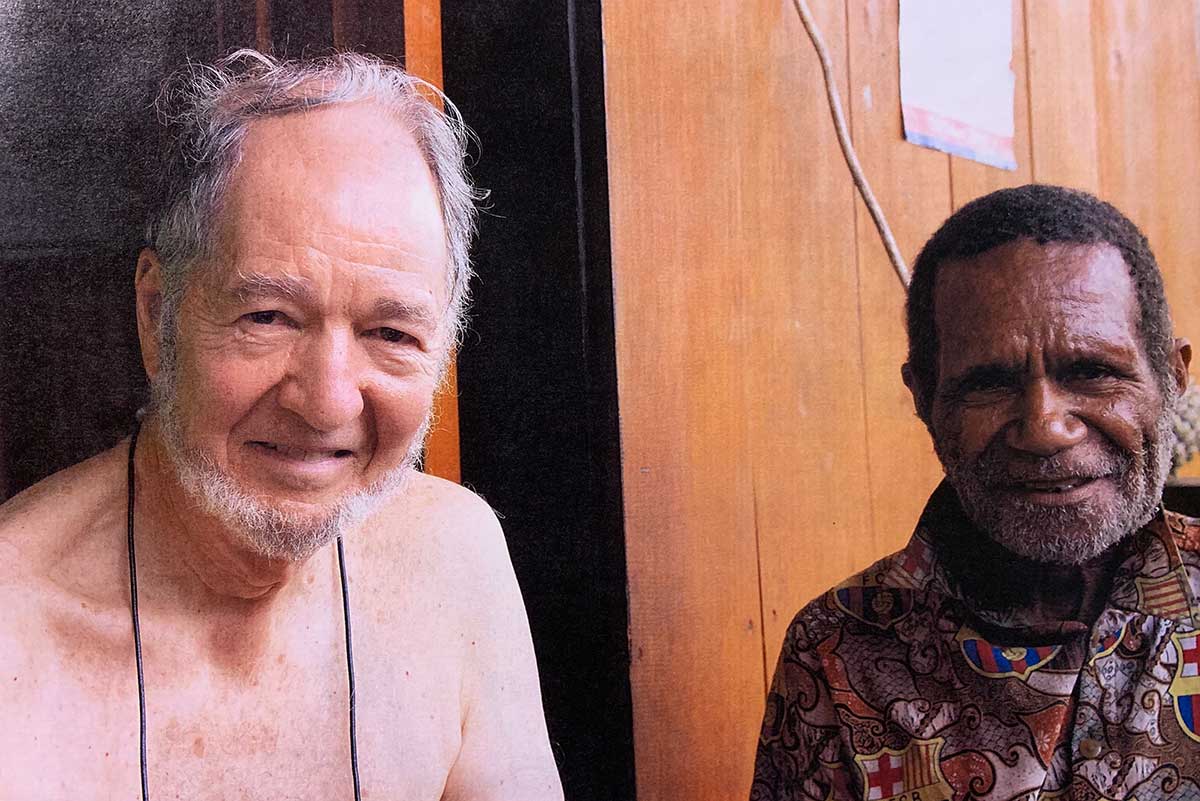

In New Guinea

The other interest I had was the environment. I began camping when I entered university and then started to get interested in the environment in general. At age 25 when I returned from Europe, a friend of mine and I spent a summer mountain climbing in Peru, and then went down to the Amazon basin to experience the jungle of the Amazon rainforest. The following year I went to New Guinea, and that’s when I became seriously interested not only in birds but also in the environment as a whole.

A Life-Changing Event and the Start of the Trilogy

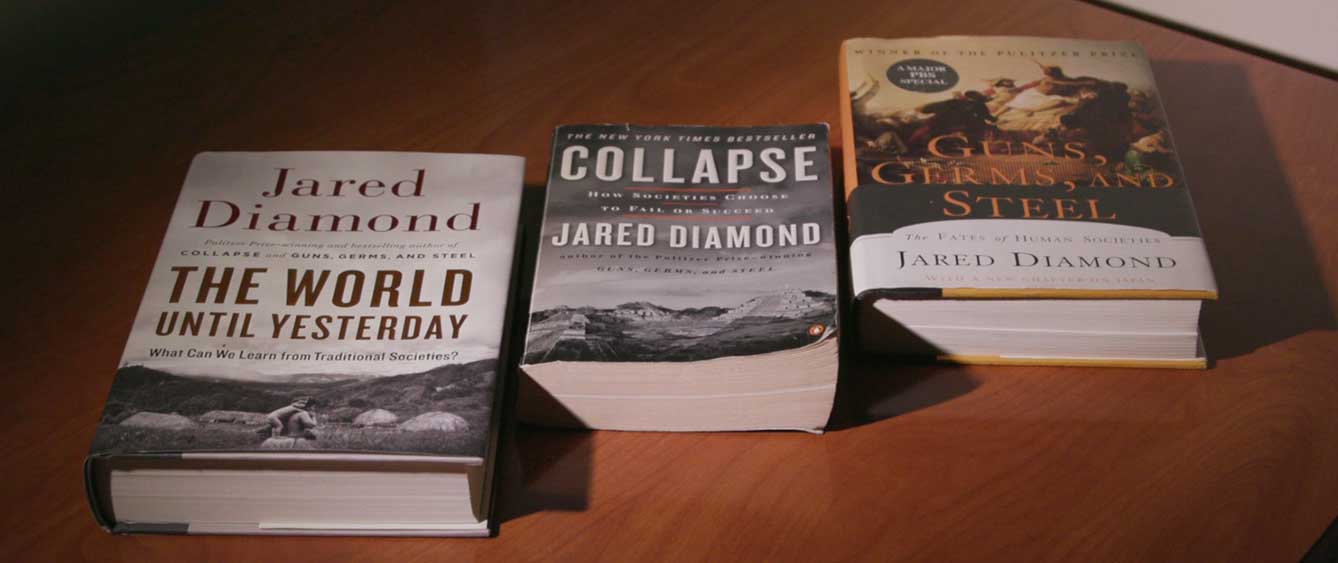

Birds, New Guinea and Guns, Germs, and Steel

In 1966 I moved from the laboratory at Harvard Medical School to UCLA Medical School. The reason I accepted their offer was that they had high regard for my physiological research and agreed that I could also continue studying birds in New Guinea, which I strongly wished to do. They also provided some research funding for it. Why am I so interested in New Guinea? There are two keywords — adventure and birds.

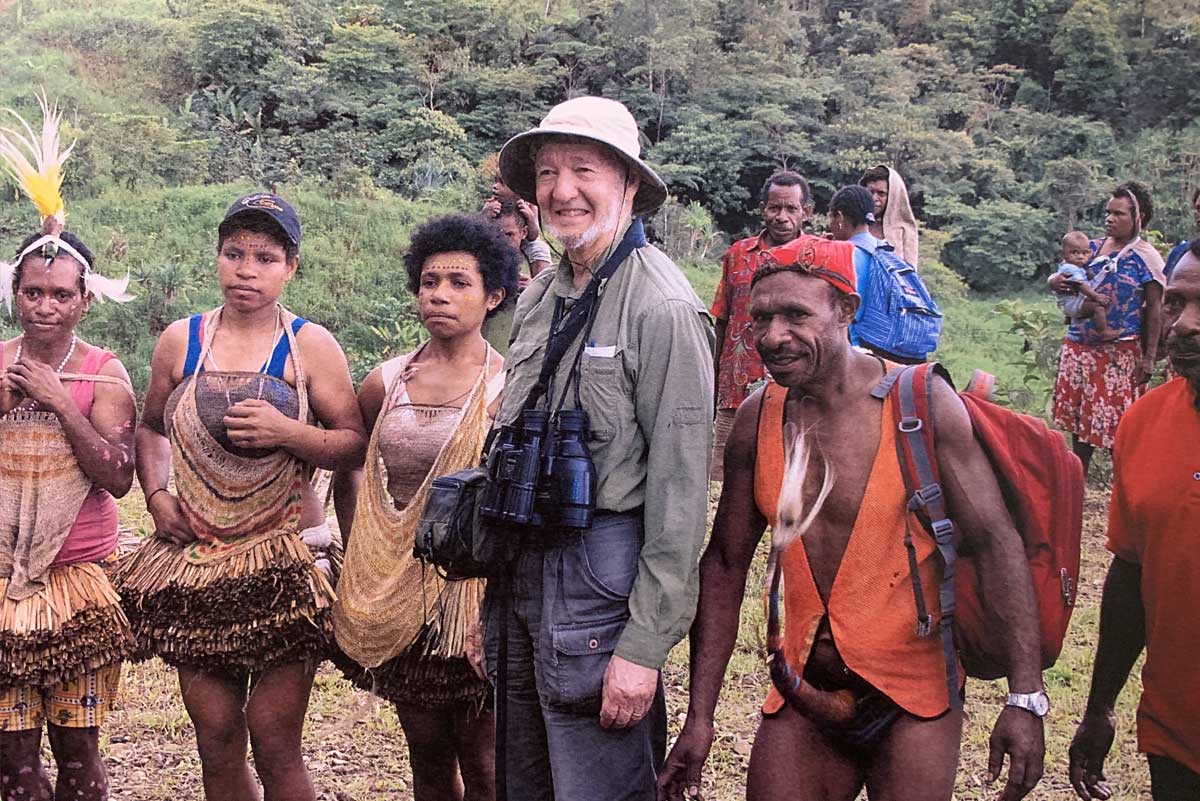

New Guinea has traditional societies still using stone tools, and there are some dangerous wild places left, so there is always a sense of adventure. It is also famous for some of the most beautiful birds in the world, the birds-of-paradise. Once you’ve been to New Guinea the rest of the world seems boring. I started visiting New Guinea in 1964, and I’ve been going back ever since, even after more than 50 years now.

With local tribe in New Guinea

When I went to New Guinea in 1972, there was an encounter which changed my view of life. I was walking on a beach when I met this New Guinean man called Yali. He asked me all sorts of questions, where I was from, what I was doing, why I was studying birds, and so on. Then finally he asked, why did Europeans come to New Guinea and why didn’t New Guineans go to Europe? Why is it that white people, Europeans, ended up with all of their "cargo" like pens, cameras and the like, and why New Guineans didn’t have "cargo"? Why did technology, civilization and metal tools develop in some parts of the world, but not in others? It’s really the biggest question of human history. And I didn’t know the answer to that question. I started to wonder, as Yali said, "Why was it so?" I thought the answer might be found in history and geography, so I started to research human origins and different farming methods. After years of research I finally published Guns, Germs, and Steel in 1997, when I was 60 years old. The main motivation which drove me to write this book was pure curiosity. It was just a very interesting yet difficult question. This book won the Pulitzer Prize in the following year, but winning a prize does not always bring you good things. In fact, my fellow physiologists who were in charge of deciding on my promotion did not know that I was studying birds alongside my study on physiology. By winning a Pulitzer Prize they realized that I was actually doing something other than just gallbladders. Some people did not appreciate it and were reluctant to give me a promotion. Fortunately, the chairman of my department supported me, so in the end it was okay.

Wisdom and Questions Brought by Multi-Sectoral Research

I am no longer active in physiology of the gallbladder but I am now a geographer and environmental researcher. I believe my experience in other fields actually helped me a lot with my current career. When you’re studying physiology, a scientist performs laboratory work by doing experiments. I would put a gallbladder it into a solution of sodium or potassium, compare and measure the results and manipulate variables.

Those are so-called manipulative experiments. So how would I do experiments on birds? When you are out in the jungle studying birds, you cannot perform manipulation experiments on them. If you want to experiment on birds first you have to catch them, and that’s difficult. Every country also has laws about catching birds. I do my own experiments on nature based on my background in laboratory experiments in physiology. I compare one mountain to another as if comparing gallbladders in a sodium or potassium and don’t need to manipulate the birds. This way, there are big advantages in studying different objectives. One can test new theories by knowing certain facts.

For example, Japan is off the coast of China and the United Kingdom is off the coast of France. You would then expect Japan and Britain to have a very similar history, but no, they’ve had very different histories. Britain’s been constantly involved with the European continent and has been invaded repeatedly. Japan has never been invaded by the continent for over 2000 years. Why are the histories of Japan and Britain so different? For example, why were farming methods developed in China and brought to Japan, and not the other way around? Such questions would not occur if I was only interested in Japanese history, and would not lead me to compare two countries and their histories. In other words, the more I know the more questions I have, but also the more capable I become in dealing with those questions. Anyone who criticizes that my interests are too broad will stand corrected. There’s everything right with being interested in lots of things.

Of course, there are things that I’m not interested in. I’m not interested in doing things to make money, such as studying and investing in the stock market. I am not fond of doing things with machinery or computers. Working in my garden doesn’t interest me much either.

Civilization and Environmental Issues

After Guns, Germs, and Steel, I got interested in yet another issue — why some societies collapse and some do not. Why has Japan, which has had an advanced society for thousands of years never collapsed, while the Maya civilization or the civilization of Easter Island has? Why did the Khmer Empire, which was once the most powerful empire in Southeast Asia collapse? Those kinds of questions.

Trilogy

When I get interested in new themes, When I get interested in new themes, I start in two ways. One is to find an expert in that field and go talk to them. Another one is to read articles, books and papers about the issue. I continue these processes until I have a hypothesis at least, something I could say that is the best guess I can make. Through these processes I have learned that a big reason behind the collapse of societies in the past was environmental problems, and not a matter of intellectual level as it has been believed. Japan is a wonderful example.

Japan during the Tokugawa era had a problem with deforestation but it did not collapse, because they learned how to manage its forests extremely well. During that era Japan essentially closed itself off from the outside world, which meant that they had to be self-sufficient in timber and supply all the wood from its own forests. In order to do this, they counted all the trees in an area of land, checked their size and calculated how many trees they can cut down. They made a forestry manual and managed wood in a sustainable manner. The Khmer empire didn’t have such a system to manage forest, and had problems with climate and water as well. Today we also have problems with the environment, forests, climate and water. What can we learn from history? In 2005, I published Collapse, and in that book I cited 12 environmental problems. One of them is the issue of climate, and although it is a pressing issue for human society, why haven’t global agreements solve it yet?

Firstly, it took a long time to establish that climate really is on average getting warmer. There are a few people who still don’t believe it. One of the reasons why it is difficult to convince some people of this is that the evidence is not direct. It’s not that I light a little fire here on my table and I can see the world’s temperature going up by a degree or two, and then when I put this fire out the world gets colder. It’s not as simple as that. The evidence is more indirect. Another reason is that we still continue to burn fossil fuels because there is a conflict of interest. There are lots of people who get rich from the burning of fossil fuels. What can be done about it? How do we solve environmental issues and advance further? People must talk about these issues and vote for governments who support solutions for climate and environmental issues; and vote against governments that oppose it. That’s all that can be done about it.

Different Society, Different Risk Management

After I wrote my book Collapse, the next theme I got into was "the things we can learn from traditional societies". Doing so many years of fieldwork in New Guinea I’ve learned the concept of how people in New Guinea bring up their own children. Other people may learn other things from New Guinea and from their tribal societies. Traditional societies, tribal societies and any societies in different countries are like large-scale experiments on how to run a human society. Each society has its own way to operate. For example, support for the arts and healthcare is better in Germany than in the United States. Likewise, there are some things that are better in the United States than in Japan.

Different traditional societies do things in different ways. How they deal with ending wars they have started, how they deal with bringing up children, and how they deal with taking care of old people. There are things that other societies do well, and some of them we can learn from to avert crisis. That was the conclusion I drew in my book The World until Yesterday published in 2012.

Towards the Future

There are two things we need to do for our future. One is to form a sustainable world.

A sustainable world is a world in which we are harvesting resources at the same rate that those resources renew themselves. Some resources such as forests, fisheries, soil, and fresh water are renewable. On the other hand, fossil fuels and metals are non-renewable resources. We can at least recycle metals but we cannot regenerate fossil fuels. So what we, the world have to do is to get more of our energy from so-called renewable sources like the sun and the wind.

The other thing would be not to ask what the best thing is for the future of our planet, because the assumption is that there’s only one thing. There are in fact so many things that are necessary for the future of our planet, not just one. We have to take good care of the environment, the atmosphere, feeding people around the world and preventing war, or nuclear war. We have to do all those things not just some of them. Suppose we take good care of the environment and solve climate change but we are finished if we have a nuclear war. Alternatively, we managed to deal with the nuclear problem, but we are finished if we have global warming and the atmosphere gets hotter and hotter. That’s why I say that the world has to stop looking for the biggest problem; there are many intertwined problems around the world and there is no order of priority.

About His Family and His New Goal

My wife Marie and I were introduced by friends of ours. We were both divorced but I had a friend whose girlfriend, who later became his wife, was studying clinical psychology in Los Angeles with Marie. The two of them figured out that Marie and I were right for each other and invited both of us to dinner at their house.

We met and liked each other, and gradually we developed our relationship, and eventually got married. We are both Jewish so we were married in my backyard by a Jewish rabbi. Marie and I are always asking each other for advice. I probably ask her for more advice than she asks me. If I have a problem with people, or with what to decide, I would ask Marie what she thinks. The title of my book, Guns, Germs, and Steel was her suggestion.

In 1987 my twin sons were born. At that point I had written some technical books about birds, but then I wondered what kind of place the world would be in 2037, when my sons are 50 years old. Will my sons have a good life or a bad one, what would the world be like? The answer won’t depend upon gallbladders; it is going to depend upon the environment. And that’s why I began to write about environmental issues rather than gallbladders.

The theme of Upheaval is how nations deal with crisis. My wife Marie is a clinical psychologist and helps people who deal with personal crisis. She tells me about how people deal with personal crisis by making selective changes. So the framework of my book Upheaval is about what we can learn by comparing personal crisis and national crisis. For the title Upheaval Marie and I struggled for probably a month to figure it out.

My future goals are probably to write another book, to continue studying ornithology in New Guinea, to keep teaching at university, to study Bach’s Cantatas, to play piano, to keep practicing Italian and German. And above all that, to spend lots of time with my wife and children and travel with my wife.

Looking back on my life, I have been able to pursue many interests, publish books and study ornithology thanks to support from my parents, good mentors, my own efforts and a little luck. I have a good life. The best thing in my life is that I have been able to help my wife and children find happiness.

His wife and his twin sons

Birdwatching in the neighborhood