A Better Future for the Planet Earth

Partha Dasgupta Interview Summary

Professor Sir Partha Dasgupta (UK)

Frank Ramsey Professor Emeritus of Economics, University of Cambridge

Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS), Fellow of the British Academy (FBA), Economist (Environmental add Resource Economics/ Development Economics)

He was born in Dhaka, Bangladesh in November 1942.

He is the son of renowned economist A. K. Dasgupta.

His wife, Carol Dasgupta is a psychotherapist.

His father-in-law is James Meade who received the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences.

Childhood

Moved from one place to another during childhood

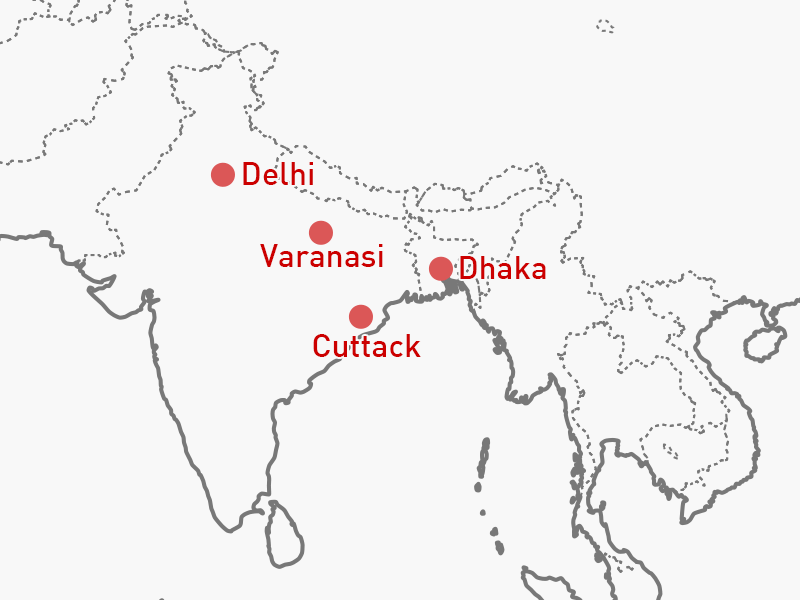

I was born in Dhaka, Bangladesh (formerly a territory of India) in 1942. I spent the first three years of my life there, but I have no memory of that part of my life because I was too young. My family moved from Dhaka to Delhi in 1946. We were the first of the diaspore when United India was divided into Pakistan and India in 1947.

I think we were in Delhi for about four or five months. I do not remember so much about Delhi either, but I think it was the time when the relationship between the Muslim and Hindu populations was strained. After that, we moved to Cuttack, which is in the eastern part of India. We lived there for about half a year, and then moved to Varanasi, a Hindu holy place, because of my father's job when I was five years old.

My earliest memories are essentially from Varanasi. Mine was a very happy childhood. My father was a Professor of Economics at Banaras Hindu University, and that afforded us a nice standard of living. We were in Varanasi until I was eight years old, but I did not attend school. My father said to me, "You didn't look as though you were interested in school, so we didn't send you." I spent a lot of time playing with the other children in the neighborhood.

Although I wasn't enrolled in a school there, my mother taught me how to read and write, and I also had a tutor who came once a week to teach Hindi and arithmetic.

I was eight when we moved to Washington D.C. My father was sent by the government to represent India at the International Monetary Fund (IMF). I started going to school in the neighborhood and learned English. My older sister, who had been living in a dormitory at school in India, lived with us in Washington D.C. It was a wonderful time for our family.

We returned to India in December of 1953. I was 11 years old and could speak English very well. My parents thought it would be very useful for me in the future to be educated in English, so they sent me to a boarding school where classes were taught in English. It was known as a good school in India, but I didn't like it. For two and a half years, I put up with it without saying anything because I thought it would be a burden for my parents to worry about whether I was happy or not. One day, I mentioned how unhappy I was. My sister talked about it with my parents, and we changed schools.

The school I was enrolled in next was unique. It was founded by Annie Besant, a theosophist, and a young Indian philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti. Jiddu Krishnaurti had a huge following all over the world, in the UK and the United States as well as in India. The teachers were followers of Krishnamurti and so were outstanding. I was very lucky to have learned from them. I grew both mentally and physically, and it was there that I developed the spirit of intellectual inquiry.

The Environment in which I was Raised

Poverty

I was raised in a world in which the rich, the comfortable and the poor intermingled. In Varanasi, there were beggars on the street, widows, orphans, elderly people, and people missing arms or legs. The full spectrum of life found expression there. I think my mother was sensitive to the poverty around us, and she did not try to shield me from this aspect of life. My father tried to understand the situation from an economic perspective.

In our immediate neighborhood, however, there was no extreme poverty. Of course, there were poor people, but they had jobs, food and shelter. Some people were much poorer than we were, but the children in the neighborhood played criket together without a thought for their different circumstances. My parents ran a very liberal household.

Religion

My family was also liberal about religion. My father was strongly agnostic. There was no religious dogma at all at our home. My mother went to a temple, but she wasn't deeply religious. It was simply a part of her life in India.

My mother took me with her when she visited the temple; and she continued to do so whenever I came home after I was grown and living abroad. She said, "I'm going to the temple to thank God for your safe arrival." I always went with her because I knew she would be pleased.

I think having a family which was not overly devout was an advantage. I've never worried about religion or experienced an existential crisis about who I am. I'm comfortable with religion as long as it is not hurting people. I have no problem with the Church of England, Hinduism, or Roman Catholic Church.

In Washington D.C. (1953)

Changes in My Life

I stayed in the United States until I was eleven years old. It was not difficult for me to adjust to life in Washington D.C. I was not restricted by religion or lifestyle. At home, we didn't eat beef or pork because Hindus don't; but the moment I was out of the house, I ate hot dogs and hamburgers because I loved them. My parents never chastised me for this.

I did not suffer from cultural shock. One of the reasons, I suspect, was my parents were emotionally secure people. So, our family life in Washington D.C. was pretty much the same as it was before. My mother cooked lovely dishes every day, and conversation in our home was very much the same as it was in Varanasi. It was only the external world that looked different.

When we first went to Washington D.C., we were dazzled by the wealth of the city and the number of automobiles. In 1950, the gap between Varanasi and Washington D.C. was greater than it is today. Varanasi was a real provincial town in a country that had just become independent. If memory serves, there were probably four cars in Varanasi. I remember that the vice-chancellor of the university had one, and maybe one or two rich families in the neighborhood had one, but everyone else we knew used rickshaws, bicycles, and horse-drawn carts. In fact, I remember clearly my sister and I counting the number of cars going one way per minute from the second floor of the apartment we lived in.

It was a huge difference, but it did not change my personal life one bit. The friends I made in Varanasi and in the United States were the same to me. Of course, they are different in their own ways, but they are the same to me. We just played together as normal kids do.

My Older Sister's Influence

My sister is five years older than I am. She is very smart, and I think I have always been influenced by her. When we were in Varanasi, she attended a boarding school founded by Rabindranath Tagore, a poet who received the Nobel Prize in Literature.

When we were living in Washington D.C., I first noticed that she read lots of books, Shakespeare, Dostoyevsky and others. Because she is older than I, I used to open her books to see what she was reading. This sparked my interest in reading. I mimicked her because I looked up to her.

We returned to India when I was eleven, and I started buying books with my pocket money. You could buy novels in those days very cheaply. They were cheap because China and the Soviet Union had strong propaganda missions. They translated Gorky and other revolutionary writers into English. I read these books, which fascinated me and improved my reading ability.

My Father's Influence

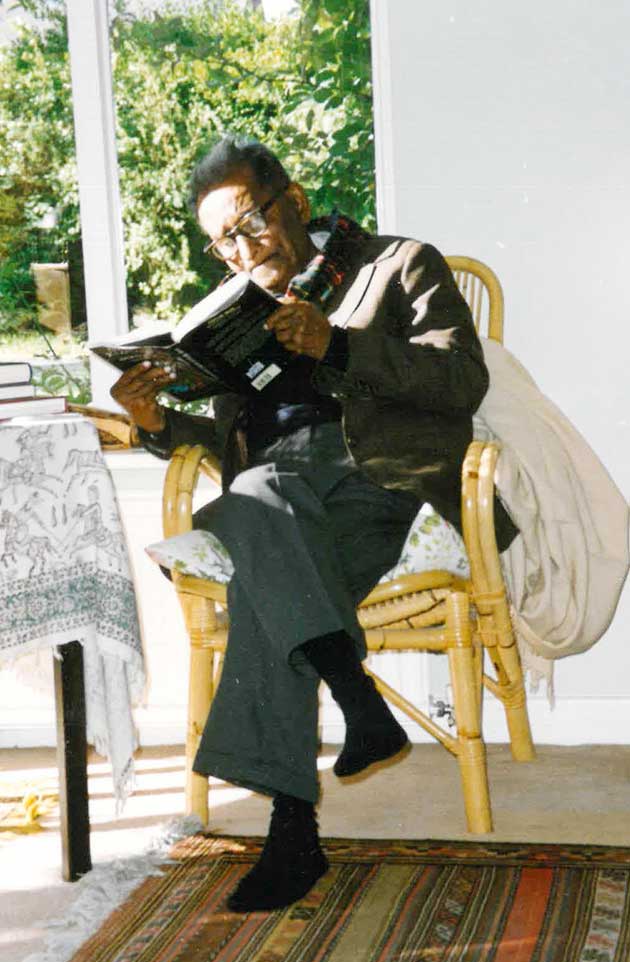

Father: The late Professor Amiya Kumar Dasgupta (1989)

My father was a real scholar. He worked very hard, but I could walk into his study at any time; and when I did, he immediately put aside whatever he was doing and chatted with me.

His influence came through conversations at lunch and dinner, and from listening to him talking with students, friends and colleagues who came to our house. I absorbed a lot of things without being aware of it. I was really curious about what they used to discuss and the way they talked.

They often talked about the stupidity and hypocrisy of politicians. He made me aware that people in high positions might say one thing but do something else. He did not, however, reject authority. He was a sufficiently disciplined thinker to know that we need authority.

What I learned from my father was to think logically based on evidence. Facts and reasons are important. No matter how loosely connected the facts may be, it is important to see them. We shouldn't reject anything off-hand because of prior convictions. I also learned to be skeptical about facts that are given to me because many things are hidden. He was truly an intellectual.

Universities: University of Delhi - Graduate School at University of Cambridge

University of Delhi (Physics)

I enrolled in the University of Delhi with a major in physics. It's not that I had a deep interest in physics. I just went along with the custom. If you were bright, you studied physics. You know, there's sort of a hierarchy; but when I started studying physics, it was very interesting and I had good teachers. The problem, though, was that although I learned skills, I don't think I grew intellectually.

University of Cambridge (Mathematics/ Economics)

After I finished my bachelor's degree, I went to Cambridge to study theoretical physics and high energy elementary particles. Since I needed to study more math as part of my preparation, I entered the math department. However, I did not follow my original plan, which was to shift from math to theoretical physics. Instead, I went into economics. There were two reasons.

One reason was that I was more interested in society. The Vietnam War was gathering stream. I spent more time with economists who were very articulate in speaking out against the misuse of power; and I gradually came to think that if I studied economics, I would understand why countries go to war.

Another reason was that theoretical physics was becoming tedious for me. I found myself doing nothing but calculations day in and day out. I didn't know why we were doing these calculations or what they were designed to give us; and I was not feeling all that enthusiastic about math.

I happened to be in a discussion group, a very famous secret society at Cambridge called the Apostles. It has a long history and some of the giants of Cambridge were members - John Maynard Keynes, Bertrand Russel, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Frank Ramsey, and other greats. One of the members was James Mirrlees. He encouraged me to study economics.

After I acquired my degree in math, I started studying economics under Professor Mirrlees. He eventually became a professor of economics at Oxford and won a Nobel Prize. He also had a math background. I think we fit together very well.

Professor Mirrlees was such a great mentor. He encouraged me to discover questions by myself while helping to keep me from going off in the wrong directions. It was very frustrating at first because I was expecting him to point me in a direction. But he never did. What he did was far more helpful.

Research Fellow at University of Cambridge - Teaching at the London School of Economics - Teaching at University of Cambridge

Encountered difficulty finding work during my time as a research fellow

After acquiring a PhD in economics in 1968, I became a research fellow, which was a post-doctorate post. Although that alleviated my financial worries, it took three years to find a permanent position. During that time, I worked at Carnegie Mellon University as a guest associate professor for a year, and at the Delhi School of Economics as a guest researcher for a year.

Although I applied for a post at University of Cambridge several times, I didn't get one. It may be because there was a strong antipathy at that time against the mathematical treatment of economics. It was summer three years later when I was hired as a lecturer by the London School of Economics (LSE).

When I was shifting from mathematics to economics, I met my wife. I knew she was the one for me the first time we met, and I asked her to marry me on our second date. It was 1968 when she graduated and I finished my PhD, and that's when we married. After we married, I spent a year at Cambridge as a researcher, a year in Pittsburg, and another year in India. I'm sure my wife had her doubts about our future.

Smooth life after starting at the London School of Economics

In Indonesia (1971)

After starting at LSE, life was very smooth. In three years, I was tenured, and my situation became stable. LSE was great for me. Senior faculty were superb, both in quality as academics and as nurturers of young minds, which was just marvelous. They let me do whatever I wanted in research and lectures, and I was promoted very fast.

Looking back, I think my teaching experience at LSE was the best thing that happened to me. If I had been hired by Cambridge, my career would have been far less interesting. It's such a prominent place, I would have been pushed into working in areas that wouldn't have been a natural fit for me. LSE allowed me to follow my interests, which helped me to become what I am now.

I returned to Cambridge as a professor of economics in 1985. When I was offered the job, my wife and I were enjoying city life in London. However, Cambridge was my alma mater and my wife was raised near there, so we decided to accept the offer.

Research Themes

PhD dissertation: Population, growth and non-transferable capital (Investigations in the theory of optimum economic growth)

The subject of my dissertation was optimum economic growth theory. I attempted a practical application of the optimal saving theory, which was probably the most active area of economic theory at that time. It was also called the Ramsey Theory. The Ramsey Theory was developed by Frank Ramsey in 1928. He died at the age of 26. In this theory, he attempted to clarify the optimal allocation of GDP to savings for future generations, and the consumption required to generate optimal overall economic welfare. This is the intergenerational welfare concept.

I worked on practical application of the sense of value proposed by Dr. Ramsey. My dissertation was entitled Population, growth and non-transferable capital (investigation of the theory of optimum economic growth) and it was published in 1968. In the last chapter, I attempted to explain how optimal savings and population measures could be achieved at the same time. This theme had been propounded by Henry Sidgwick and my father-in-law, James Meade; but I provided a more detailed analysis and explanation. That was something really novel, I'm still very proud of it, and feel it really is one of the best things I've done.

What is the optimal population? How many kids can I have? If you have one more child, then you have to save more and you have to invest more. I formulated such a trade-off. I also introduced land into the model. I hadn't thought it necessary to include nature in the model, but the idea led to my subsequent research; and I came to understand its importance as time passed.

This is my research style. My ideas develop gradually. I chase a problem; and in the process of solving it, I observe something else, and move in a slightly different direction. So, I look back from time to time to see if the ideas I have been considering are related to one another and might be trying to send me a message. That's how it's happened with me. I never have a grand plan, but results accumulate little by little.

Opening the door to sustainability (1974)

In 1974, Geoffrey Heal, then professor at the University of Sussex and currently professor at Colombia University, and I published a paper entitled The Optimal Depletion of Exhaustible Resources. Because coal and petroleum are limited resources, current consumption has an impact on future production.

Considering exhaustible resources as a constraint condition, we tried to clarify the optimal consumption path theoretically. This study was influenced by the oil crisis that occurred at the end of 1973.

Our idea opened the way to the concept of sustainability that came along much later. I believe we laid the groundwork for it, but it wasn't seen by economists at that time as anything more than a wrinkle in the existing concept.

Shifting research to renewable resources (= nature) (End of 1970s - Beginning of 1980s)

After publishing the book with Professor Heal, I felt that it was essential to heighten the public's awareness of the need for action. The action should be a shift toward renewable resources. At that time, I started reading books on ecology, and these helped to clarify my thinking.

Forests, rivers, and other renewable resources are natural cleansing processes at work, but they are finite. So you can interrupt them, but it's not inevitable. You have a choice.

For example, if we use too much water, water resources are going to degrade. If we moderate consumption, we can maintain a reasonable balance. It's the same with forests. Timber is renewable; but if we log too much, then the forest recedes. The carbon problem is a special case of what I'm discussing because we are looking at the atmosphere as a renewable resource; but if we overburden the system, it can't recover. It deteriorates.

What I did between the late 1970s and early 1980s was shift to the study of renewable resources. When I was satisfied with the mathematics side of it, I started working on the institutional side.

Integration of environmental and development economics (1980s - 1990s)

Looking into renewable resources, I found that they were related to systems and social norms. For example, depending on the water management system we choose, water resources may or may not be degraded. Continuing my research, I really started understanding the link between nature and poverty.

Our institutions are greatly influenced by the natural environment in which we live. It might be said that the environment forms institutions. For example, people living in mountain areas have different marriage customs than people living in river valleys, hunter-gathers in semi-arid areas, and people who live in the arctic do. This has been studied in anthropology, but it is also a concern for economics.

I worked on this theme in the 1980s and 1990s. Nobody in economics was studying this at the time. Essentially, I was inspired by my geography teacher at the school founded by Krishnamurti. He taught me geography as an analytical, empirical subject rather than as a simple collection of unrelated facts. He didn't merely ask us to remember the names of countries and their capitals. Instead, he encouraged us consider what kind of clothing people in an area would be wearing, what food would they be eating, or what lifestyle they would have.

I applied this method to economics. I tried to understand how people in the villages of Africa get the water, fuel, or herbs that are essential to their daily lives. I observed such details and gathered data in an attempt to explain the overall economy.

I wasn't the first to ask how we could construct a macro economy from a large numbers of individual household economies. These were all seen in the market economy, but what I was seeing was a world in which markets hardly ever existed. It was a world in which people depended on social norms, not on institutions, a world with expectations placed on individual behavior and penalties for not meeting those expectations.

In such a society, you've got real differences among regions. In a market economy, there is no difference. There's a price for a product, and there is supply and demand. If supply doesn't equal demand, there is a reason that can be given. The economy is standardized. The market in Australia is the same as the market in the United States; but in a society that depends on social norms, systems differ greatly from region to region.

I studied poverty with the characteristics of each community in mind. This helped to explain poverty better than the normal models did. I was teaching at Cambridge at that time, and had significant help from outstanding anthropologists and biologists on staff.

Shifting my research from exhaustible resources to renewable resources (= nature), I noticed the importance of poverty as an issue. If I did not understand how people impact nature, I could not understand how nature responds to people. If I did not understand how poor people cope with nature, I could not really understand poverty. In this way I naturally introduced poverty and nature into economics.

Many people think that it is impossible to reduce poverty and protect the environment at the same time. One reason we think there must be a conflict between the two is that we use mental models to understand poverty which don't really have nature in them. I knew that they were related because the depth of poverty in rural areas of sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia was so tied up with the degradation of their local environments. Therefore, we must consider both at the same time.

Inclusive Wealth Index

I explained the basic concept of the Inclusive Wealth Index (IWI) in Are We Consuming Too Much? This was published in the Journal of Economic Perspectives in 2004. I developed this concept with Karl-Goran Maler to explain the advantage of measuring "wealth" in evaluating whether the economy is progressing or regressing.

Corporations issue profit and loss statements, and balance sheets, which forms the basis for evaluating the value of their stock. What we showed was that countries' national accounts really ought to have a parallel set of data for their assets. GDP looks at the flow of consumption and investment only. In order to measure the economy of a country, it is also necessary to check the value of its stock.

Let's take a look at the example of forests. Forests offer value, timber, fruit, and so forth. That's the flow. We use what forests produce (stock), which is akin to depreciating capital. Now, if the rate of depreciation exceeds a certain point, then you're in trouble because you're encroaching on the stock, which influences future production.

Now, the question is, "what is an asset?" Assets include natural capital, ecosystem, artificial capital, human welfare, human wisdom, and so forth. First, we inventory our natural capital. Natural capital includes forest cover, wetlands, estuaries fisheries, and so forth; and then we attempt to place a value on them, and then put them on a par with other forms of capital assets like buildings, roads and so forth. The aggregate is what we should identify as going up or down. In other words, we try to measure sustainability by determining whether the value of the stock is increasing or decreasing.

The report on the Inclusive Wealth Index was issued by the International Human Dimensions Program (IHDP) of the United Nations University. I was the chairman of the scientific board. We tried to actually put some numbers on forests, agricultural land, sub-soil resources, and fisheries for each country. We also assigned a price to carbon, for example, $50 or $100 per ton; and we saw how the numbers shaped up to show if wealth has changed.

The latest version, published in 2014, includes data on approximately 140 countries. Now, I may be getting the numbers wrong because I don't have them at hand; but there was a substantial number, something like 40 or so countries, for which per capita wealth had decreased while per capita GDP had increased.

Unfortunately, we lack data for lots of natural capital, including ecosystems; and this capital is precisely the kind that you would expect to be degrading at a faster rate. Therefore, each country should have its own national account of "wealth" that includes as much natural capital as possible. I helped India to do this.

We've only got one Earth; however, if we continue consuming resources at the current level, it is estimated that we will consume the equivalent of the amount contained in one and a half Earths. A lot of resources are produced by nature, but we consume more than nature produces, which reduces the stock. We are encroaching on wetlands by building shopping malls, converting nature into concrete. Everybody is happy because they can shop more; but you've lost a bit of natural capital.

We need to decrease consumption. We at least need to change our current pattern of consumption. If we take more than is produced, stock decreases. Unless the value of other assets increases, our wealth is going to decline.

Economics and Environmental Issues - Is the world changing for the better?

I was involved in the reformation of India's national accounting system by implementing the IWI concept under Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. We often call the system "Green National Accounting," which includes not only nature, but also human capital such as education, health, and so forth, even with the idea of reclassifying them within the accounting system. We created a report and submitted it to the government of India in 2013.

I'm an academic, and my work ends when I submit a report. I can suggest options available for decision-makers, but I cannot tell them what to do. I've heard, though, that the system in India has been functioning well. I worked with the head of the government's statistical unit. We provided a roadmap for changes to the accounting system based on what they would be able to do in two, four, and 10 years. Following the plan, they are working on changing the system. I am not sure how much they have accomplished, but my proposals are still used by them.

Will this be a model and example that other countries can pick up on? I do not know. It all depends on the mood of the nation, whether they want it. All discussions about economic progress are built around growth and GDP. The concept of nature is put aside. For example, when we have a water problem in California, we think about what to do. When we think about the progress of nations, on the other hand, we never think about water. We do not connect such issues with the economy. One of the large-scale issues is climate change, which, however, is not dealt with in economics.

I would like to change this tendency. I have said so for a long time. I think nature is sort of like going to church; on Sundays we care about these important things, but by Monday you're back to making money or you're in the city. I'm talking now about the part of the world I live in.

In economics, unfortunately, we do not consider nature as a central theme. Students want to get good grades and a good job. They then tend to go into research in major fields. Although they care about nature and are against the expansion of toll roads, they tend to think about their own research, regardless of whether it is in fact valuable.

Education is important in the pursuit of change. Nature studies should be as integral to our educational programs as reading, writing, and arithmetic are. Children should know insects, bats and other creatures we may recoil from, not just the nature we find in the zoo. They help pollination and decompose waste that we create. We really need to understand these things.

There are some movements that integrate economics with environmental and ecological studies. Although it was long ago, back in 1991, I became the chair of the scientific advisory board of the Beijer International Institute for Ecological Economics of the Royal Swedish Academy of Science. Half of the members were ecologists and the other half were economists.

The ecologists said, "Yes, we need you guys because we can't articulate the problems. We know the symptoms, but we don't know how they articulate, and we can't produce a cure." I, on the other hand, said the social scientists need the ecologists and the environmental scientists in a big way because we don't know what the world looks like, how nature works. How are you going to prescribe policies that bear on nature if you don't know the processes by which nature responds to humans? So, that collaboration, I think, went well and could achieve an integration of natural sciences and economics.

On the whole, I think I've seen more of an acceptance and welcoming attitude from the natural scientists; they would love to have more economists join them. Economists, mainstream economics, are rather dismissive of these guys; but I know both young and not so young colleagues have done wonderful work at the interface of ecology and economics.

However, it's sporadic and it's sparse. It may take some more time for the people at the top of departments of economics in the world to recognize the importance of the work done by such people.