A Better Future for the Planet Earth

Pavan Sukhdev Interview Summary

Mr. Pavan Sukhdev (India)

Green Economist

Born in New Delhi, India (March 30, 1960)

UNEP Goodwill Ambassador

Founding Trustee of the Green Indian States Trust (GIST)

Founder & CEO of GIST Advisory

Associate Fellow of Davenport College, Yale University

Childhood

Childhood Surrounded by a Wealth of Nature

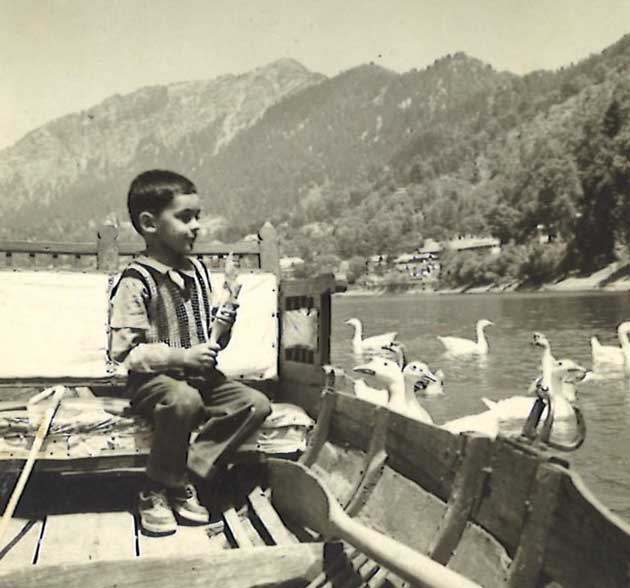

I was born in New Delhi, India, in 1960. New Delhi was much smaller then. At my grandmother’s house we could hear the jackals howling from the thick hedges at night and the fruit bats flocking around the trees during the day. Nature was everywhere. During summer vacation, my family visited a lot of places in India, places such as Shimla, Nainital and Mussoorie, and enjoyed a pleasant time surrounded by beautiful nature every year. That was more than 40 years ago. It was amazing and precious to have spent my childhood in unspoiled nature.

In Nainital (1966)

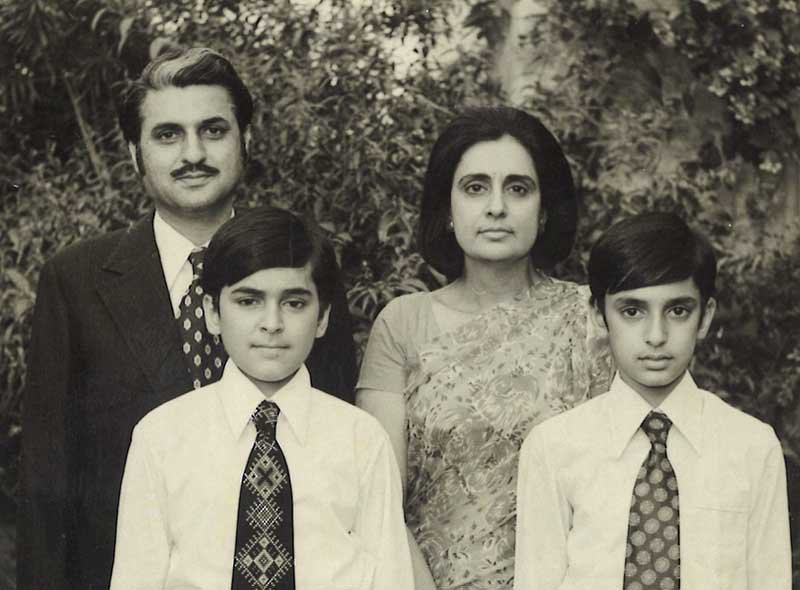

Philosophy and Ambitions Taught by Parents

First row, left (1974)

My father was a police officer and my mother was a housewife. She was very clever and taught me to value of pursuing real nature of things. She used to say, "Whatever it is that you are doing, do the best you can"; and that has driven my ambition to ensure that I always deliver best quality. My father taught me very important moral lessons, especially those regarding work. From him, I learned that hard work is its own reward. Although it is wonderful to achieve something through your effort, I also learned that hard work itself is valuable and worth admiring. That’s been my guiding philosophy in life.

As a Student

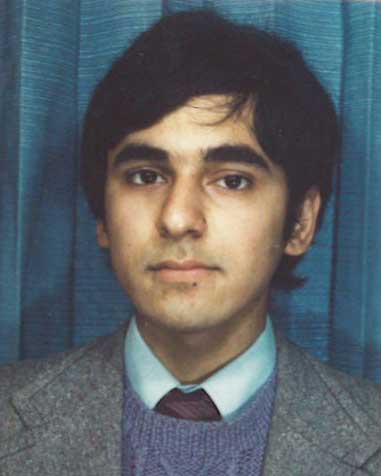

From India to Switzerland and England

When I was at St. Columba’s High School in New Delhi, I was the top student in my class. My father was transferred to Switzerland in 1974, so our family moved to Geneva, where I studied at the Collège du Léman. However, three years later, I moved to Dover College in England to study English. There I grew independent and learned about the world and life. In 1981, I was awarded a scholarship to study physics at Oxford University; but Oxford University was a place of diverse opportunities and I also became interested in social anthropology; and I even attended lectures on Buddhism by the world-renowned professor Richard Gombrich.

At Dover College (1977)

From Physics to Economics

I was disappointed that I could not get the money I needed to study what I wanted. Even though I had a scholarship, it did not completely cover my education - it was only 60 pounds a year. I began to believe that money mattered, and that I must make sure I earned lots of money. I gave up physics and went into economics, aiming to become an accountant, and studied finance, accounting, and law. They were totally new areas for a young scientist.

The one thing in particular that fascinated me in economics was "externalities"*1 because as a physicist, there are no "externalities." If it is really big, then it’s astrophysics. If it’s small, it’s atomic physics. If it’s tinier, then it’s subatomic and particle physics. There are no "externalities." However, when you come to "economics",*2 the moment you get into natural capital for example, you run into "externalities." You end up making assumptions and models which do not in fact reflect reality. I found that aspect of economics quite bizarre. In physics or in the natural sciences, if an experiment does not conform to the theory, you throw the theory away. In economics, if an experiment does not conform to the theory, you discard the experiment! I just couldn’t get my head around this. Nevertheless, I used my experience in accounting and my facility in Mathematics and English to get myself a nice job as a banker, and I forgot about "externalities" for a while.

*1 : The areas that are not covered by conventional economics, which only deals with market prices and considers economic rationality. (Pollutions, etc.)

*2 : Conventional economics. Hereafter "economics" refers to the conventional economics.

Becoming a Banker

I was a typical young person in India in the 70’s and 80’s. I wanted to be a doctor, a lawyer or a banker to earn a nice income. In 1983, I was hired by Australia New Zealand Bank. My first year was spent in training in all the different departments. After that, I became a trader, something I did for the next 10 years. Among other tasks, I helped develop the bank’s systems for treasury and investment banking. I then handled a wide range of areas, including derivatives trading, currency options, interest rate options, disposal of non-performing loans. Because of my experience in these areas, I was hired by Deutsche Bank in India in 1994. I was involved in the development of a new global market business that handled credit, stocks, foreign exchange, and interest. I was selected to be the chief operating officer for global markets in Asia, and I became the director of finance for the Asia-Pacific Region. In 2003, I moved to London as the chief operating officer for the global emerging markets division at Deutsche Bank.

I was a banker most of my time, and that experience helped me in my later career. I knew how to read balance sheets and understand what a company is and does. It was important that I understood business strategies and risks to recognize the role of sustainability at the business level. Secondly, it helped me to understand both the strengths and weaknesses of markets. Many people think that markets can solve all problems. Markets are great at discovering prices and allocating capital efficiently, but they are not great at solving social problems. There are things that markets can do and things that markets cannot do. I could understand markets and finance, and that was a huge benefit of having worked in banking. The third benefit of being a banker was respect in society. I’m not saying it’s a good thing that someone simply respects the managing director of a bank because of his position or his seniority, but that’s the way our society is.

What I got from my daughters

My first daughter, Mahima, was born in 1988. We were living in Mumbai, which is a difficult city to find nature in. She was passionate about nature and would sit at the Bombay canal staring at the budgerigars for hours. When she became bored with that, I had to find her other things in nature; and that is how my own love for nature slowly came back.

My second daughter, Ashima, was a recycler. She was saying "lee-cycle" before she started talking. I made my daughters a doll’s house out of used cardboard that was about to be thrown away. They enjoyed playing with it for a long time. Nature and recycling were already part of my family, and that thought stayed with me and gave me great joy and inspiration as my passion for environmental economics increased and my work progressed.

Left: Mahima Right: Ashima (2015)

Awaking to Environmental Economics

Natural and Social Capital - Realizing the Significance of Externalities that had been Ignored by Environmental Economics

When I was the chief operating officer for global markets in Asia, a friend of mine living in Singapore asked me what money was and why some things were worth money and other things were not. In answering my friend’s question, I realized we had gotten our system so badly wrong. Just to say, "This is about externalities," is not an explanation. It is an excuse because in reality you cannot ignore today’s massive externalities, factors such as the economic value of public goods and services, things like natural and social capital. We needed to have a system that recognizes externalities that reflect the reality that surrounds us. This led to my reading more on the subject of environmental economics - the works of David Pearce and Ed Barbier, Karl-Göran Maler *3, Partha Dasgupta (winner of Blue Planet Prize 2015), and Herman Daly (winner of Blue Planet Prize 2014). These are my gurus. Their books taught me what was wrong with our economic model and gave me some ideas about what could be done to solve this central problem.

*3 : One of the authorities on environmental economics. Received the Volvo Environmental Prize (Sweden) in 2002.

Weak Points in GDP and the Need for Environmental Accounting

I had been very interested in the idea that we were not accounting for wealth correctly. We look at GDP at the national level, and profits at the corporate level. In GDP, we don’t account for the creation of human capital (by acquiring knowledge and skill training), we don’t account for water pollution due to the loss of forests or the degradation of soil fertility. We don’t account for any of that, and this causes the destruction of assets, especially natural capital, which results in poverty. Nature is fundamental to the well-being of the poor in India. Whose cows and goats will not get leaf litter to eat from the forest if the forest is lost? Whose fields will not get their nutrients and the fresh water that comes from the forest if the forest is lost? It is the poor farmers. By destroying forests, we destroy the GDP of the poor, who rely on the benefits of natural resources. I realized that green accounting at the national level was really important. Otherwise my country, India, would think that it was making progress because its GDP was increasing, whereas in fact they would be destroying the assets of the poor.

Encounter with Professor David Pearce

I then thought of making a proposal to the experts. Because I had read some of the work by Professor David Pearce, I attended one of his public lectures when I was in London and gave him my 7-page proposal about environmental accounting.

I was worried that he might think it was cheeky and stupid of me, but to my surprise he liked it. He was very kind to agree to meet with me. We discussed the paper and the proposal. I felt that our meeting encouraged me because such a world-leader in this area did not reject the idea as stupid. This was in 2003 when I was 43 years old.

He gave me some wise advice and connected me with a few other experts such as Dr. Giles Atkinson *4, whom I could speak to. I only met him three times in my life, but I feel as if he had lived in my mind for several decades because I had read so much of his work. It was primarily because of Professor Pearce, who was extremely intelligent and very kind, that green accounting became my passion.

*4 : A professor at the London School of Economics. Familiar with environmental economics and environmental policies.

Establishment of the Green Indian States Trust (GIST)

Encouraged by Mahatma Gandhi and Friends

After meeting with Professor Pearce, I had an idea to create the Green Accounting for Indian States Project (GAISP). I set up the Green Indian States Trust (GIST) a NGO India as the first step. GIST measures the changes in natural and human capital in India, all of the changes that were invisible and were not being reflected in the state accounts or at the national accounting level; but I didn’t have the courage to start it myself because I was worried. What would it mean to my career? Would I be able to do this? Where could I get funding? How would this affect my family’s future? I remember one evening in Mumbai when I was thinking about how to get this project set up. I noticed a sign that said, "Find purpose, the means shall follow," a quote from Mahatma Gandhi. That hit me solidly. I said to myself, "Oh, my God, I have found my purpose, so the means should follow."

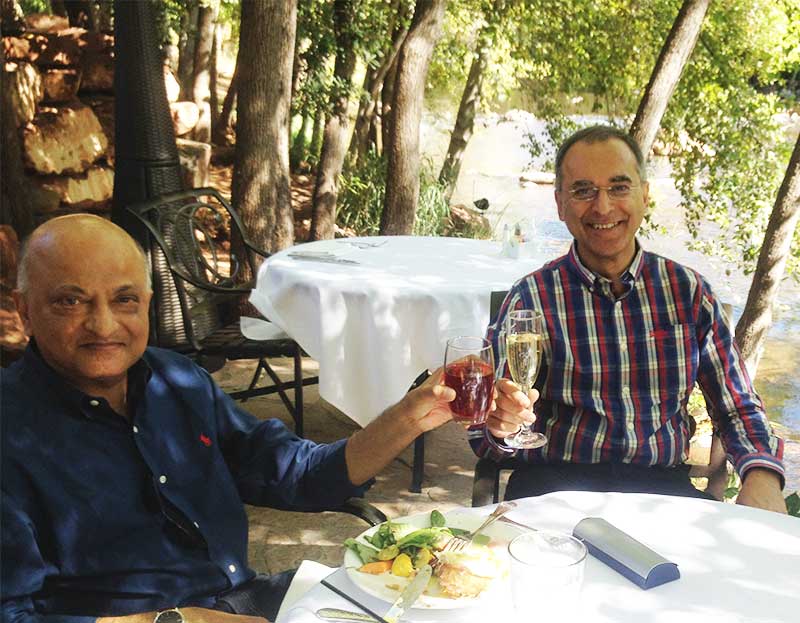

With the late Rajiv Shinha (2014)

This experience prompted me call my friend Yasuthasen (a Consultant at the Foreign Exchange). "I have an idea for green accounting for Indian states. Will you help me?" As I explained, he said, "That’s wonderful, of course I will help you." I also spoke to my friend, the late Rajiv Shinha (Professor of Marketing at the Arizona State University, USA), and Sanjeev Sanyal (a financial economist, Singapore), both of whom were excited about the idea as well. This is how I established GIST with my three friends. So the means really did, as Gandhi said, follow.

Achievements by GIST

As GIST quantified ecosystem services and calculated the GDP of each state in India, we found there were states which were losing 10 to 20, even 30 percent of their GDP in terms of the value of natural capital lost every year. These losses were quite significant and, of course, invisible because they weren’t being accounted for in the balance sheet of the state or the nation. While GIST was quantifying natural and human capital, the Central Empowered Committee (CEC) of the Supreme Court of India used our valuation of natural capital in 2006 to calculate compensation for the destroyed forest areas. The Supreme Court used the multiple of five times for nature reserves in India, and the multiple of ten times for national parks because of the uniqueness of their biodiversity. This was one very good result of our work. Moreover, I think it has created awareness that conserving nature and advancing human development are not trade-offs. If you do not conserve nature, you damage the "GDP of the poor" and you cannot have sustainable development.

From GIST to TEEB (The Economics of Ecosystem and Biodiversity)

Selected as the TEEB Leader

TEEB, the Economics of Ecosystem and Biodiversity, is a global project called for at the G8+5 Environment Ministers’ Meeting held in Potsdam in 2007. The idea for TEEB developed because some people presented copies of our GIST Monographs to the European Commission. That is why the government of Germany and the EU Commission asked me to lead the TEEB project. I had two careers from 2003, one was my job at Deutsche Bank, and the other was my private career in green accounting. When I became the TEEB leader, I did my jobs at Deutsche Bank and TEEB together, and I delivered the Interim Report. For the final TEEB report, however, I realized it would be just too difficult to handle both jobs at the same time. So I took a two-year sabbatical to concentrate on TEEB.

TEEB Activities

The TEEB Interim Report was presented at the COP9 of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), which took place in Bonn, Germany in 2008. The main purpose of the Interim Report was to pull together the state of knowledge on the ongoing loss of ecosystems and biodiversity, and the state of knowledge on the economic and social impacts of that loss. In response to a request from the European Commission, TEEB calculated estimates of the loss of natural capital in large cities, and we learned that the effective loss of natural capital was between two and five trillion dollars per year. We presented this result in the same year that Lehman Brothers declared bankruptcy, which was also around two to five trillion dollars. I pointed out that we had been losing this much of this natural capital every year for the last few decades. How come people were not concerned about this? I think it was vital that some people finally understood the scale of the problem.

Evaluation of Ecosystem Services and TEEB Proposal

What is the economic and social value of ecosystem services? For example, forests absorb CO2 and reduce the risk of climate change. They release water vapor into the air and help to create rainfall, which in turn creates crop productivity around the world. This also creates fertile soil. These are the functions of the forest and the ecosystem services provided by forests. Such forest functions have economic value for humankind. This is the benefit that forests provide.

For example, the value of bee-based pollination of fruit crops around the world is around 200 billion dollars, or 150 billion euros, which is almost 10-20% of the total value of agriculture. That is how much value bees provide. Of course, this is free. Bees never send you an invoice, and this is why we don’t think about how important their pollination services are. It is crucial to explain to policymakers the importance of such free benefits. They would never destroy bridges, factories, or roads. Because they have economic value based on market prices, they are in the balance sheets; but they assign no value to this hugely important "natural capital" because it doesn’t charge for it. This does not, however, mean you can disrespect or you destroy nature. We must respect and conserve it by recognizing its value. It is important to understand that nature has tangible value and to make biodiversity and ecosystem services visible through economic valuation.

The TEEB project at the national level helps us to understand, measure and assign value to ecosystem services that have been provided by nature. Likewise, the TEEB project at the corporate level helps find ways of identifying, measuring, and assigning value to the dependency and impact of corporations on natural capital. TEEB helps decision makers to understand and measure those values, and to reflect those values and costs to their decision making. No development is sustainable without the protection of natural capital. We want people to have freedom to develop, not the freedom to destroy themselves.

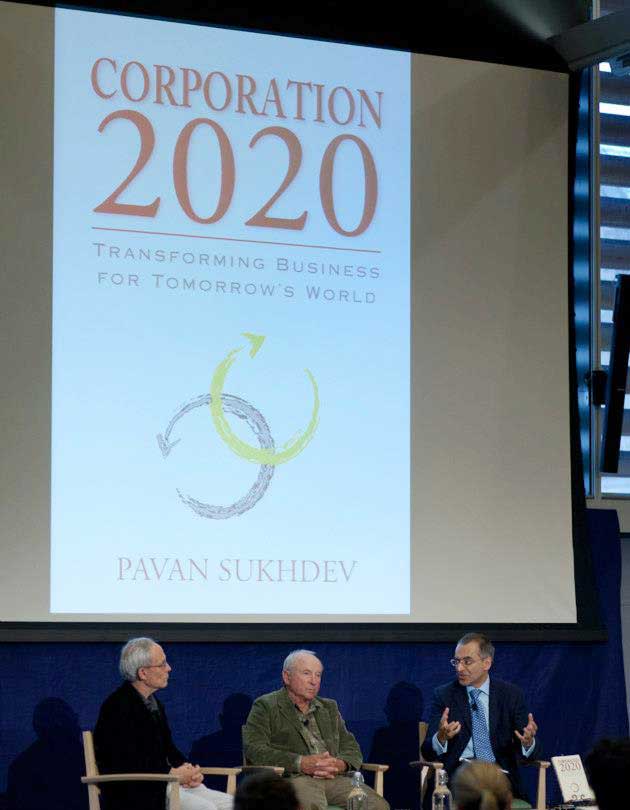

Publication of Corporation in 2020 - Leadership for the Future

From Banker to Environmental Economist

The final full TEEB report was presented at COP10, Nagoya, Japan in 2010. During that time, I became the lead author and head of the "Green Economy Initiative" for the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Our goal was to demonstrate to the Meeting of Ministers in Nairobi in February 2011 that an inclusive green economy was the only way we could truly achieve the goals of sustainable development. I then finished my work as TEEB study leader and Head of UNEP’s Green Economy Initiative. I had to think about whether I wanted to return to my job at Deutsche Bank. I really didn’t want to because by this time, my life had become that of an environmental economist and I was passionate about what I was doing. I knew I had to keep doing this because I had found my purpose. You cannot change when you have found purpose. You stay with it. I spoke with Dean Peter Crane of the Forestry and Environment School of Yale University about teaching TEEB at the post-graduate level. At the same time, I wrote "Corporation 2020" with Yale University’s kind support.

Companies must change

The corporation is an extremely important institution. Two-thirds of the economy and jobs are in the private sector, and the corporation, which is the mainstay of the private sector, needs to change. I called my project "Corporation 2020" because I thought there was not that much time to make these changes happen. The earth’s environment, including the climate and ecosystem, has deteriorated and is close to its limit. We must do something now because 10 or 20 years from now will be too late.

A typical corporation in the present day ("Corporation 1920") excels in achieving positive results in the areas of financial value, physical capital, value for shareholders, and maybe also achieves some positives in the area of human capital by training its employees, but results in producing negatives in social and natural capital. The problem, though, is that it creates private profit at the expense of public loss.

Tomorrow’s corporation, Corporation 2020, should see plus or zero in every category of capital - not just for shareholders, but for stakeholders. We cannot manage what we do not measure; so to achieve this kind of corporation, accounting for externalities becomes most important. Some call this "True Cost Accounting," which calculates not just traditional profit and loss, but integrated profit and loss that includes natural land social capital. These are the things we need in order to measure corporate performance. Some leading companies have already begun to implement them. Through the "Corporation 2020" campaign, we want to promote the new kind of corporation, one which creates private profit and at the same time supports society by creating public gains in natural, human, and social capital.

My Final Purpose & Message

In July 2016, I was invited to participate in the launch of the Natural Capital Protocol created by the Natural Capital Coalition, the former TEEB Business Coalition. The coalition has more than 200 corporate members, more than 450 contributors, and already 50 companies have agreed to implement the protocol. I had tears in my eyes as I looked at the companies and what they were doing, and I was so pleased to see that they were working on doing the right thing. Even 200 companies, however, are not enough. There are hundreds of thousands of companies in the world and we need every one of them to do this.

I hope national accounting agencies like the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) will offer them the framework and enough support on methodologies to measure and publish impacts on nature and society. I have a very urgent message to corporate leaders. Some may think that they will be respected in the future for generating profits, but they are wrong. I would like to say to them, please understand your externalities, discover them, measure them, assign value to them, manage them, and please disclose them. The final purpose is to achieve a society which is driven by good, by respect for human capital, human wealth, respect for natural capital, natural wealth, and for social capital and social wealth.

I have two daughters and I want to ensure that they can enjoy the benefits of nature as much as I or my parents did, and that their children and their children’s children can continue to enjoy the value that nature provides to humanity. We have to learn to live in harmony with nature.