af Magazine

~The Asahi Glass Foundation’s web magazine on the global environment~

We Cannot Achieve Sustainable Societal Wellbeing Without Ecosystem Services

Professor Robert Costanza, a dual citizen of the United States and Australia, shocked the world in 1997 by publishing a paper that first demonstrated that value of ecosystem services exceeding the total global GDP at that time. As a co-founder of ecological economics, he has long advocated for the importance of ecosystem services. For these achievements, he was awarded the 2024 Blue Planet Prize. During his recent visit to Japan, Professor Costanza stated, "Understanding and communicating the value of intact healthy ecosystems and the services they provide to humanity can lead to a sustainable wellbeing future."

(Reconstructed from an interview on May 15, 2024 and a commemorative lecture on October 24, 2024.)

Ecological economics is a new field of study that recognizes that the economy is embedded in society and the rest of nature.

"The society we are living in now is in a new era called the 'Anthropocene.' - to emphasize the magnitude of human impact on our ecological life-support system. The impact of humans on the Earth system has so large that six out of the nine 'planetary boundaries' are currently outside the safe operating space for humanity. We are approaching multiple tipping points and action is necessary for us to live on a stable planet. If we choose the so-called 'business-as-usual' scenario, there will be no sustainable future for us. However, many people currently choose to ignore these inconvenient truths and instead opts for the comforting lie that GDP growth will solve all of our problems. We now need a new narrative, which begins with the understanding that the economy is embedded in society and the rest of nature," said Professor Costanza.

Along with the late Professor Herman Daly, one of the 2014 Blue Planet Prize laureates, Costanza is known as co-founder of the transdisciplinary field of ecological economics. Traditional economics positioned ecosystems outside the market and considered that current economic activities could continue indefinitely. Costanza and others believe that, given Earth's finite nature, there are limits to economic activities as well. Costanza and Daly founded the field of ecological economics, which bridges the gap between the market and the ecosystems in which it is embedded and on which it depends, initiating research to evaluate ecosystem services that benefit our lives. In the paper "The value of the world's ecosystem services and natural capital," published in the science journal Nature in 1997, Costanza and colleagues estimated that the global value of these services averaged US$33 trillion per year in 1995. This figure exceeded the global GDP of US$18 trillion at the time.

Currently, research on ecosystem services is actively conducted worldwide. According to Costanza, more than 6,000 papers on this topic are published annually, with the total number nearing 60,000. Among these 60,000 papers, the most frequently cited one is the paper just mentioned by Costanza and his colleagues.

Their estimation results received significant media coverage at the time, with Nature featuring the headline 'Pricing the Planet' on its cover. While it was useful to attract attention, the professor noted that, 'The phrase 'pricing the planet' led to misunderstandings."

"There are quite a few people who interpret ecosystem services as a human-centered concept. Such people think of putting a price on the services nature provides, aiming to turn them into items for trade, linking them with privatization, commodification, and commercialization. This is a misunderstanding. We are discussing a 'system framework' that explores the interactions between humans and the rest of nature and reveals how humans depend on nature, not a one-way narrative of humans that receive exploitive services from nature. A more accurate headline would have been 'Valuing the Planet,'" says Costanza.

Distributing Resources 'Just Right' for Everyone and Enhancing Quality of Life for All

Until now, many countries around the world have pursued GDP growth as their primary policy goal. However, Costanza emphasizes that we now need a new perspective, one that doesn't rely solely on GDP growth. The concept of 'well-being' serves as a clue to this shift. Comprised of 'well' and 'being,' it has become an increasingly prominent keyword for the society of the future, and we are hearing it mentioned more frequently in various contexts.

"Translating 'well-being' into Japanese can be challenging, but it can perhaps be rephrased as 'quality of life.' The ideal state we should aim for is one in which everyone maintains a high quality of life within sustainable limits. To achieve this, we need to distribute resources fairly and efficiently. This fairness should extend not only to those of us alive today but also to future generations and to other species.

This approach is grounded in the concept of a steady-state economy--not too big, not too small. The right size is key, within planetary boundaries" Costanza stated.

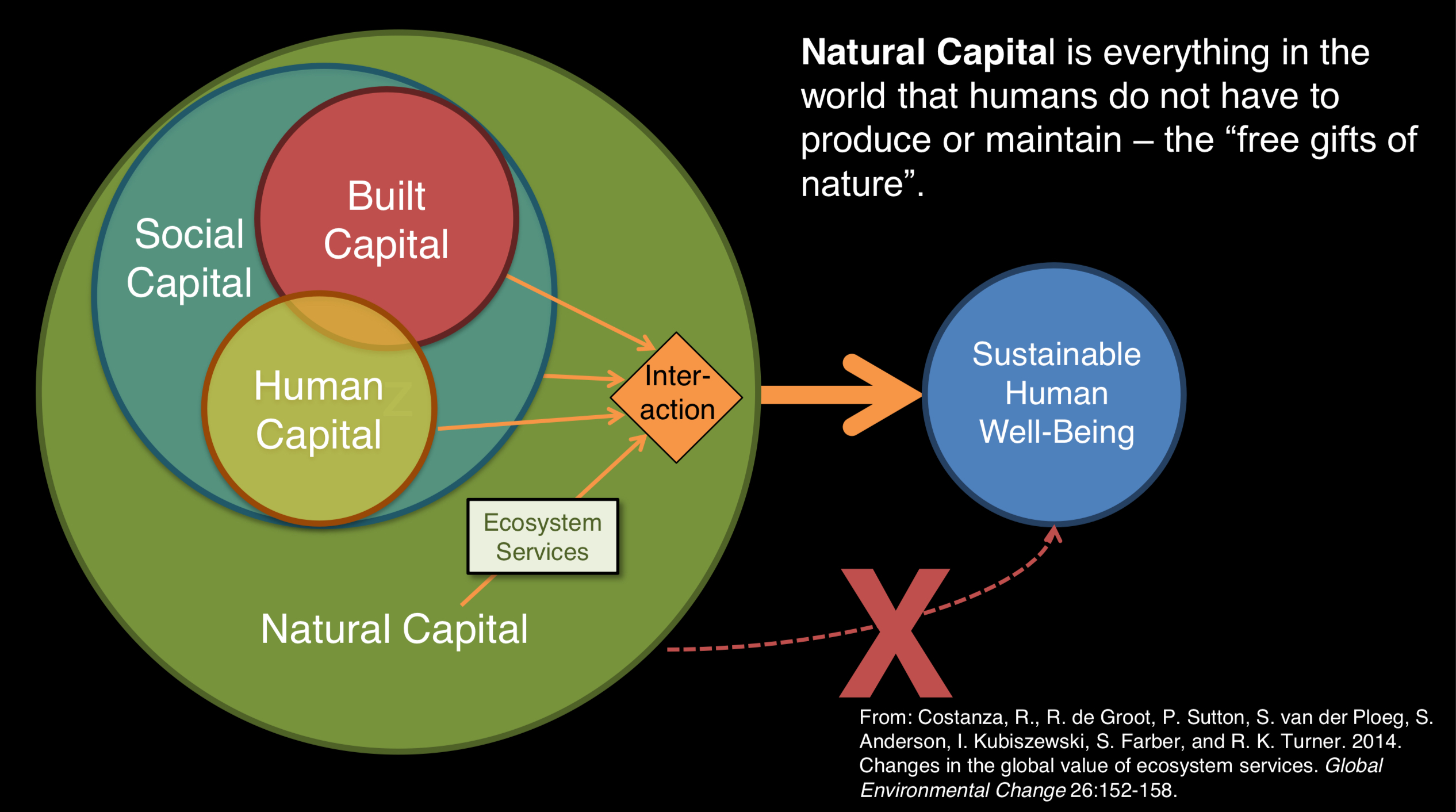

"A steady-state economy refers to an economy that does not aim for economic growth as the primary goal. It means 'an economy where active economic activities take place but the scale itself does not expand.' This concept, proposed by the late Professor Herman Daly, one of the 2014 Blue Planet Prize laureates, is a fundamental idea in ecological economics. If everyone shares and distributes resources in just the right amount, the quality of life for all will improve." Costanza explains that natural capital and ecosystem services are one of the main things that support this improved quality of life.

"Ecosystem services and quality of life are connected through the four major types of capital assets that support all human wellbeing: built capital, human capital, social capital, and natural capital. The quality of life increases when all of these four capitals are in good condition and balanced. Moreover, the four types of capital constantly influence each other."

Changes in Land Use Have Resulted in a $20 Trillion Loss in Ecosystem Services. We Need New Indicators to Replace GDP.

The evaluation of ecosystem services conducted by Costanza and his colleagues has become an important reference point for considering the four types of capital and quality of life.

"I know that evaluating ecosystem services in monetary terms is not a perfect valuation. It is just one of several possible approaches. However, the biggest mistake is not considering them at all. The impact of valuing ecosystem services has been significant. It has raised public awareness, provided a foundation for research, and assisted in the formulation of policies and measures. Additionally, I believe that being able to measure changes over time is also a significant benefit."

For example, how has the value of ecosystem services changed between 1997 and 2014? The most significant change over those 17 years was due to land use changes, such as desertification, loss of wetlands and loss of coral reefs. These changes greatly altered the global value of ecosystem services. When estimated in monetary terms, this resulted in a loss of about $20 trillion/yr. "However, there is no need to be overly pessimistic," Costanza says. "It is still possible to achieve ecosystem recovery by 2030 through policy reforms and significant transformations. Our actions can restore the value of ecosystem services."

According to the professor, changes are leading to losses not only in natural capital but also in social capital. Income inequality is increasing, and many people are unable to establish sustainable relationships with others or access healthcare or other basic services. The decline in the well-being of these individuals cannot be captured by the GDP metric, which does not measure how GDP is distributed among the population.

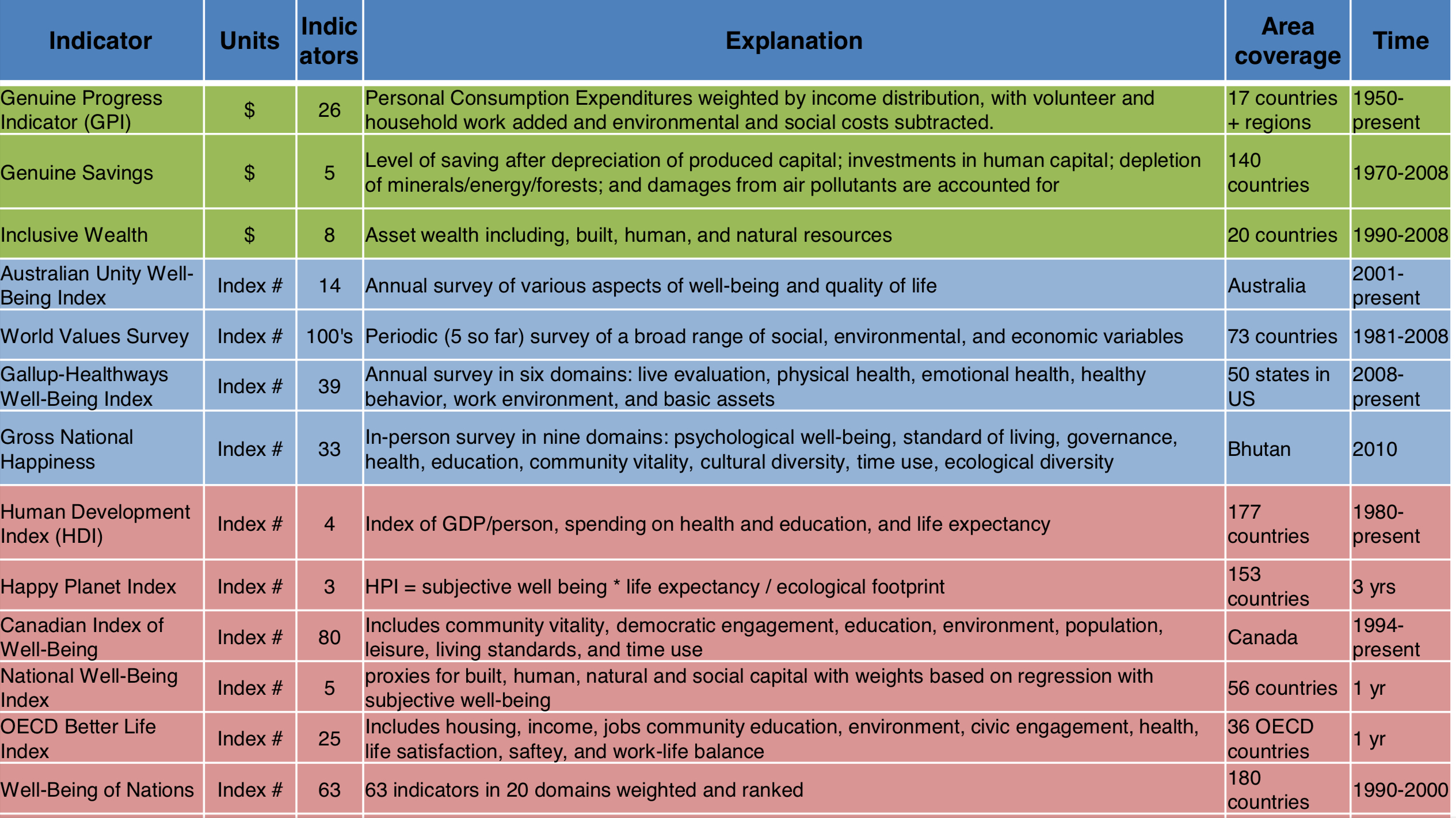

"The world's per capita GDP is steadily increasing, but how much impact does it have on our individual wellbeing? GDP is not the only component that contributes to life satisfaction. Social roles, healthy life expectancy, and other factors are also important. Some research indicates that GDP only contributes about 15% to explaining differences in survey-based life satisfaction across countries. But this study did not include the contribution of natural capital to satisfaction. The time has come for us to depart from GDP and find more comprehensive metrics of well-being. The UN's Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) can also be considered one of the metrics in this regard," says Professor Costanza.

A New System for Managing Natural Capital and Social Capital, Along with Social Remedies to Heal Systemic Addiction, is Necessary.

"The world I want to create is one that is fairer and filled with people who appreciate the importance of the natural world. I want to see a world where wealth is distributed more equitably, free from the misplaced over-reliance on GDP. I also want to achieve fairness for my generation, younger generations, and children," says Costanza. He emphasizes that a new system for managing shared common assets, such as natural capital and social capital, is necessary to move toward the future he envisions.

"One way to manage shared common assets is by entrusting them to a reliable organization, where resources like water, land, and human connections are held in common rather than privately owned. Evaluating ecosystem services can also help us determine how much of these shared assets should be preserved for future generations," says Costanza. He also believes that a crucial step towards creating a just world that values ecosystem services is to treat our societal addiction to the system of consumerism and GDP growth at all costs.

Professor Costanza continued, "Research shows that people who place a high value on material possessions often have health issues and are not as happy as others. The mindset that they must consume more to reach the same level as their neighbors or buy higher-quality items is a trap of the system and an addiction. I believe we need to change these goal settings and motivations. We should provide them with experiences that genuinely enhance their quality of life and encourage them to break free from the competition for more goods. The desire to possess more and better things should shift to a vision where having just enough--not too much or too little--is sufficient. Humans are highly adaptable creatures, so behavioral change can definitely occur."

In the face of global environmental issues, Professor Costanza reassured us, saying, "A world where everyone is happy and fulfilled is definitely achievable." The field of ecological economics, which he and his colleagues have developed to connect the economy and the rest of nature while encompassing the entire world, is truly the intelligence and ideology needed in this era. By using the professor's vision as a guiding light, we should consider and act on what we can do in our respective places. Beyond that, a well-being future surely awaits us.

Profile

Professor Robert Costanza, USA & Australia

One of the two 2024 Blue Planet Prize recipients

Ecological Economics at the Institute for Global Prosperity, University College London

In a groundbreaking 1997 paper, Professor Costanza and colleagues demonstrated, for the first time, that the ecosystem services provided by nature to humans far exceed the economic value of the world's GDP at that time. This work brought global attention to the previously understated importance of ecosystem services. As a co-founder of ecological economics, a transdisciplinary field of study that recognizes that the economy is embedded in society and the rest of nature, Professor Costanza actively advocates for an ecologically sustainable, wellbeing society.